Tuesday, 20 August 2013

Being a gay poet in Iran: ‘Writing on the edge of crisis’

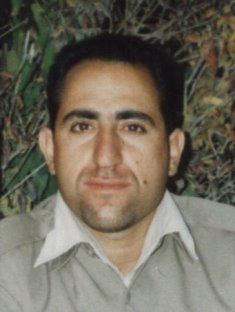

Not everyone is optimistic about the election of Iran’s new president. This article by Nogaam, a publisher of censored Iranian authors, explains why gay poet Payam Feili doesn’t share the optimism of his peers.

Iran’s government has been increasing pressure on writers and artists over the past few years, but its heavy hand does not strike evenly.

Iranian poet Payam Feili, who is a gay man, is the victim of a brutal system. He was fired from his job, his translator’s house was ransacked, and the censors have shunned him.

Isolated in Iran, Feili has dedicated himself to writing. He says he lives among his ideas, a citizen of his mind: “I’m writing on the edge of crisis but I think I am doing fine. I’ve gotten used to life being full of tension, horror, disruption and crisis”.

Born in 1983, in Kermanshah, a city in western Iran, Feili has faced insurmountable obstacles as an author who, with pen as sword, is fighting back against social, cultural and political taboos. Despite the endorsement of renowned Iranian Simin Behbahani and the backing of one of Iran’s biggest publishers, Feili’s work has only once emerged from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance with a seal of approval.

Feili’s first book, ‘The Sun’s Platform’, was published in Iran in 2005, but dozens of other works submitted to the ministry have been refused publishing permission. Payam is blacklisted, not just for his words, but for his sexual orientation.

“They refused my books, one after the other, without any explanation. They have a blacklist of authors who are simply not allowed to publish anything. Even my apolitical non-religious works, works of pure poetry, were banned. There’s nothing scary about them, but the state authorities are afraid of everything”

Observing his sharply delicate words falling from the pages of history unread, Feili began publishing his books outside Iran, knowing all too well that he was endangering himself. Officers from the Ministry of Intelligence ransacked his translator’s house and threatened him, forcing him to sever ties with Feili. After gaining notoriety abroad, the company Feili had worked for fired him without good cause. With the odds stacked against him, Feili insists on exercising his right to freedom of speech.

“If you read my books, it’s obvious I have not succumbed to self-censorship. My poems are bold and fearless. I don’t allow anybody, not me, not others, not even the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance to censor my books”

Many are hoping for Rouhani’s presidency to bring around the cultural thaw that characterised Khatami’s two terms. Feili has not been swept up by the wave of hope that has captured his peers.

“Nothing essential has changed. The structure is still the same. It’s a play, a comic and ugly performance. They’re relying on the naivety of people to be able to succeed”

Embittered by 30 years of living in exile within the borders of his country, as a homosexual, and as a writer that challenges the status quo, Feili is now dedicating his time to securing funding to translate his poetry for audiences outside Iran.

“I’ve learned a lot and I know what’s going on in Iran. I know that when my homosexual narrative is woven through my words and there is a Star of David on the cover of my book, the censors won’t even bother opening it to find out what is inside. I just want to be published. I know the audience outside Iran is different, but I just want to be heard”.

This article was reported by Nogaam, a publisher of Iranian books and authors that have been censored, banned or blacklisted. Nogaam relies on donations from readers to publish their books for free download on their website. Payam Feili’s book ‘White Field’ was first published in Persian by Nogaam in London in July 2013. The publisher is currently seeking support to help Payam translate his poems, and fulfil his simple goal of being heard.

I Will Grow, I Will Bear fruit … Figs (First Chapter)

ONE

I am twenty one. I am a homosexual. I like the afternoon sun.

My Apartment is in the outskirts of town. Near the wharf. In a place that is the realm of seashells, the realm of corals, adjacent to the eternal sorrow of the turtles.

My mother lives in the waters. In the remains of an old ship. On a bed of seaweed. Her hair blazes like a silver crown above her head. My mother is always naked. She visits me every now and then. At my apartment in the outskirts of town.

She first crosses the wharf. She floats in the scattered scents of the bazaar. Then she pays a visit to the crowd of fishermen in the seaside cafés. Among their wares, a hidden pearl. And she leaves them and heads for my bed. Of course, along this entire route, she is no less naked.

Poker; that is what I call him. He is my only friend. We met during military training. He is twenty-one. He likes the afternoon sun and he is not a homosexual.

I consider this a threat. I have never talked to anyone about my sexual inclination. In fact, I hide it. Even from my few sexual partners. With them, I pretend it is my first such experience.

My sexual partners are night prowlers. Strangers. Poker is not a night prowler. Poker is not a stranger. And this is chipping away at me from the inside!

Payam Feili

Bahai world News: “Five Years Too Many” campaign leads to global outpouring of support

A global outpouring of support and concern for the plight of the seven Iranian Baha’i leaders – and for the situation of other prisoners of conscience in Iran – marked worldwide commemorations of the fifth anniversary of the arrest of these Baha’is.

Statements calling for the immediate release of the seven came from every continent, issued by government officials, religious leaders, human rights activists, and ordinary citizens during 10 days in May as part of the “Five Years Too Many” campaign. Local and national media reports also carried news of the campaign around the world.

“Our hope is that the government of Iran will understand clearly that the seven Baha’i prisoners, who have been unjustly and wrongfully held for five long years simply for their religious beliefs, have not been forgotten,” said Diane Ala’i, the Baha’i International Community’s representative to the United Nations in Geneva.

“Our ultimate hope, of course, is that Iran will immediately release the seven – and all other prisoners of conscience in Iran,” said Ms. Ala’i.

As the campaign came to a conclusion, one theme that emerged was the degree to which religious leaders around the world find Iran’s persecution of Baha’is unconscionable.

In South Africa, Shaykh Achmat Sedick, vice president of the national Muslim Judicial Council, used a Five Years Too Many campaign event on 15 May to talk about freedom of religion from an Islamic perspective. He described how the teachings of the Qur’an support religious freedom – and added that Iran’s persecution of the Baha’i community is entirely unjust.

On 14 May, some 50 religious leaders representing virtually every religious community in the United Kingdom sent a letter to UK Foreign Secretary William Hague, calling on him to demand that Iran immediately release the seven.

Signatories to the letter included Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury; Jonathan Sacks, Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth; and Shaykh Ibrahim Mogra, an Assistant Secretary General of the Muslim Council of Britain.

“Iran has abandoned every legal, moral, spiritual and humanitarian standard, routinely violating the human rights of its citizens,” they wrote. “The government’s shocking treatment of its religious minorities is of particular concern to us as people of faith.”

And in Uganda, the Inter-Religious Council issued a joint statement with the Baha’i community there calling on Iran to respect the fundamental human rights of Iranian Baha’is.

“These sheer violations of basic human rights of Iran’s religious minorities by the regime of that country gave rise

to international outrage from governments and civil society organizations and all freedom-loving people worldwide,” said Joshua Kitakule, Secretary General of the Council, on 15 May in Kampala.

Other significant responses during the final days of the campaign included:

● A letter calling for the “immediate release of the seven” by prominent people in India, signed by L. K. Advani, chairman of Bharatiya Janata Party; Soli Sorabjee, former Attorney General of India; Imam Umer Ahmed Ilyasi, Chief Imam of the All India Organization of Imams of Mosques; and Miloon Kothari, former UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing, among others.

● A series of statements issued by prominent Austrians in support of the seven, including one by Efgani Donmez, the first Muslim elected to the Austrian Parliament, who said “The Baha’is in Iran are part of the society, part of the Iranian culture. They should also have the rights as all the other citizens in Iran.”

● A speech in Ireland by campaigner and Holocaust survivor Tomi Reichental, who said the discrimination faced by Iranian Baha’is sadly reminded him of what happened to the Jews in Nazi Germany. “I can very well identify with the struggle that the Baha’i religion suffers in Iran,” said Mr. Reichental on 15 May in Dublin.

● A video message by Nico Schrijver, a member of the Senate of the Netherlands and vice-chairperson of the Geneva-based UN Committee for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, who said: “The leaders of the Baha’i community have been detained for the sole reason that they are Baha’is. This is of course a complete violation of human rights law.”

The campaign, which ran 5-15 May, quickly found support from others, including Australia’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Senator Bob Carr, and Lloyd Axworthy, former Minister of Foreign Affairs in Canada, as previously reported.

Among the most notable expressions of concern was a joint press release. by four UN human rights experts, issued on 13 May, which stated that the seven are held solely because of their religious beliefs, that their continued imprisonment is unjust and wrongful, and that Iran’s treatment of religious minorities violates international law.

Six of the seven Baha’i leaders were arrested on 14 May 2008 in a series of early morning raids in Tehran. The seventh had been detained two months earlier on 5 March 2008.

Since their arrests, the seven leaders – whose names are Fariba Kamalabadi, Jamaloddin Khanjani, Afif Naeimi, Saeid Rezaie, Mahvash Sabet, Behrouz Tavakkoli, and Vahid Tizfahm – have been subject to an entirely flawed judicial process, and were ultimately sentenced to 20 years imprisonment, the longest of any current prisoners of conscience in Iran.

Further details can be found at the campaign website, located at: http://www.bic.org/fiveyears.

OMCT: Group calls for release of jailed Iranian journalist brothers

The Observatory reports that Khosro Kordpur was arrested on March 7, 2013 in Mahabad, and two days later the Ministry of Intelligence arrested his brother, Massoud Kordpour.

They were then reportedly taken to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) detention centre in Uroumiyeh, where they were kept in solitary confinement.

On April 25, they were finally allowed a visit by family members, who reported that they had not been interrogated during their 45 days of arrest.

Khosro Kordpur went on a 25-day hunger strike to protest his undetermined condition.

They were finally transferred back to Mahabad on June 26, at which point the two brothers had lost between 10 and 20 kilos, and they were finally charged with "enmity against God."

The brothers are also charged with "crimes against national security, propaganda against the regime and insulting the leader."

Khosro Kordpour has challenged the charges against him, saying all the material published by his news agency has been within the framework of the law. Massoud Kordpour also defended himself, saying that, as a reporter, he has only exercised his constitutional right to report on issues.

The Observatory reports that the request for bail for the two brothers is pending the judge's decision, which was not given in court, and their second hearing is to take place in September.

Reuters: Iran's Arab minority drawn into Middle East unrest

The blast, two days after new President Hassan Rohani took office, hit a pipeline feeding a petrochemicals plant in the city of Mahshahr in Iran's southwest, home to most of its oil reserves and to a population of ethnic Arabs, known as Ahwazis for the main town in the area.

The Ahwazi Arabs are a small minority in mainly ethnic Persian Iran, some of whom see themselves as under Persian "occupation" and want independence or autonomy. They are a cause célèbre across the Arab world, where escalating ethnic and sectarian rivalry with Iran now fuels the wars in Syria and Iraq and is behind political unrest from Beirut to Bahrain.

Tehran dismisses any suggestion that discontent is rife among its Arab minority, describing such reports as part of a foreign plot to steal the oil that lies beneath its Gulf coastal territory. Iranian news agencies reported a fire on the gas pipeline last week but said its cause was unknown.

There has been unrest in the area for many years, and now some Ahwazis see themselves as part of a larger struggle between Shi'ite Iran and the Sunni-ruled Arab states across the Gulf, which back opposing sides in the Syrian civil war.

Although the overwhelming majority of Ahwazis are Shi'ites, some say they sympathize with the mainly-Sunni rebels fighting Syria's Iran-backed President Bashar al-Assad.

"Our land is occupied and the Syrian people are in the shadow of a dictatorial regime that serves Iranian interests in the region," said an Ahwazi activist speaking from inside the region. "If Bashar falls, Iran falls: that is the slogan of the Ahwazis," he said.

ARABISTAN

The Islamic Republic would almost certainly outlast Assad's downfall. But the slogan nonetheless shows how events in Syria are stirring a latent threat to stability in one of the world's most resource-rich corners: the Iranian province of Khuzestan, once known as Arabistan for its Arab majority.

An Ahwazi militant group said it had sabotaged the pipeline with homemade explosive devices, targeting Iran's economy in revenge for the authorities' mistreatment of ethnic Arabs and for Tehran's roles in Syria and Iraq.

"This heroic operation is a message to the Persian enemy that the national Ahwazi resistance has the ability and initiative to deliver painful blows to all the installations of the Persian enemy, inside Ahwaz and out," the Mohiuddin Al Nasser Martyrs Brigade, which has claimed responsibility for previous attacks on energy infrastructure, said in a statement.

The group threatened to intensify its activities in coordination with members of Iran's Kurdish and Baluch minorities, some of whom also complain of unfair treatment.

Arabistan was a semi-autonomous sheikhdom until 1925, when it was brought under central Iranian government control and later renamed, marking the start of what some Ahwazis describe as a systematic campaign to Persianise if not obliterate them.

According to the CIA Factbook, Arabs make up about 2 percent of Iran's population, suggesting there are around 1.6 million of them, a small minority in a country with a Persian majority and much larger Azeri and Kurdish communities, among others.

At their most ambitious, Ahwazis want an independent state stretching beyond the borders of Khuzestan, which is at the head of the strategic Gulf waterway and shares a border with Iraq.

Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein's attempt to annex Khuzestan triggered the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s in which a million people were killed. "Liberating" the Ahwazis was a slogan for Saddam and the Arab states that supported him.

In 1980, with Iraqi support, Ahwazi separatists took 26 hostages in Iran's London embassy. British special forces stormed the embassy after a six day siege; two hostages and five captors were killed.

Thousands of Ahwazis crossed into Iraq during the Iran-Iraq war and some were given land, but they are no longer welcome under the Shi'ite-dominated government that rose to power after U.S.-led forces invaded in 2003 and toppled Saddam.

Exploited by avowed secular Arab nationalists like Saddam, Ahwaz is now being woven into the sectarian narrative revolving around the Syrian conflict, which has polarized Sunnis and Shi'ites. Ahwazis are overwhelmingly Shi'ite, but in recent years there has been some conversion to Sunni Islam among them.

"I converted for political reasons and I think most are like that," said the activist contacted by Reuters in Khuzestan, who decided to become Sunni during a trip to a Shi'ite shrine in the Iranian city of Mashhad after hearing several ethnic Persians travelling on the same train mock Arabs.

Iran's Deputy Minister for Arab and Foreign Affairs Hossein Amir Abdollahian told reporters in Kuwait there were no Sunnis in Khuzestan. Nevertheless, Sunnis across the Arab world have taken up the Ahwazi cause with zeal.

From a stage in the Iraqi province of Anbar, where Sunnis have rallied for months against a Shi'ite leadership they denounce as a stooge of Iran, lawmaker Ahmed al-Alwani roared: "We tell our people in Ahwaz: we are coming!"

In Bahrain, whose Sunni monarchy blames Tehran for fomenting protests by the Shi'ite majority on the island since 2011, a street in the capital has been renamed "Arabian Ahwaz Avenue".

A bearded presenter on Saudi-based hardline Sunni pan-Arab TV channel al-Wesal burst into tears recounting the sufferings of the Ahwazi people: "We must stand with them as Muslims! They are calling us," he said after composing himself.

One battalion of the rebel Free Syrian Army is called the "Ahwaz Brigade", although the group says there are no foreign fighters in its ranks.

"We have relations with different factions of the (Syrian) rebels," said Habib Nabgan, the former head of a coalition of Ahwazi parties whose armed wing carried out last week's pipeline attack.

"They need information, which we give them, and we need some of their expertise, so there is cooperation and that is developing," he told Reuters via telephone from Denmark, where he took refuge in 2006.

PROTESTS

The use of Ahwaz for sectarian and Arab nationalist agendas has served to justify repression by Iranian authorities, which say they face a foreign plot to control the country's natural resources. Tehran has accused Britain, Israel and Saudi Arabia of provoking unrest in Khuzestan.

Although the bulk of Iran's 137 billion barrel oil reserves lie beneath the soil of Khuzestan, most Ahwazis struggle to scratch a living off the land they lay claim to.

"We get nothing from the oil and gas fields except smoke (from the refineries)," said activist Taha al-Haidari, in footage filmed secretly in prison before he was executed along with two of his brothers and a friend.

They were arrested after taking part in a protest in 2011 and convicted of "enmity against God" and "corruption on earth", having confessed under duress to murder and being members of an armed separatist group, one of them said in the video.

The authenticity of the tape, which activists said was smuggled out of jail, could not be independently verified.

Iran dismisses Ahwazi grievances and says reports of their mistreatment are mere propaganda, often pointing out that a former Iranian minister of defense was an ethnic Arab.

A document purporting to be a secret government directive leaked in 2005 described a policy to dilute the Arabs of Khuzestan by displacing them and encouraging others to settle there. The letter, which authorities said was forged, ignited protests that were put down by force, leaving at least 31 dead, according to rights group Amnesty International.

As the anniversary of that crackdown approached in 2011, Ahwazi activists began calling for a "Day of Rage" in the spirit of popular anti-government revolts in Egypt and Tunisia.

Protests broke out but were quelled by authorities who have since rounded up dozens of Ahwazi activists, at least five of whom are currently awaiting execution on terrorism-related charges, rights groups say.

Ahwazi groups are divided over whether to seek independence or devolution of power within a democratic, federal Iran.

"We have a right to seek independence, but is that possible at this time? I don't think so," said Abu Khaled, a member of the biggest Ahwazi federalist party, speaking in Dubai.

"We have to be pragmatists, or else we will be a part of history, like the Red Indians (Native Americans)".

(Editing by Peter Graff)

The guardian: Iran plays the blame game

Long-term instability in Iran is an alarming prospect for western countries keen to resolve disputes over the country's nuclear programme and other contentious issues. But continuing political weakness in Tehran is also likely to produce the opposite effect – increased regime concern about external attempts to interfere, destabilise, and exploit its current vulnerabilities. This paranoid trend threatens unpredictable, even dangerous consequences – but may be justified.

The pinning of blame for Iran's post-election turmoil on malign foreign enemies is already under way among so-called principalist, conservative factions. The pro-Ahmadinejad Keyhan newspaper today denounced plots by "politically bankrupt dictators" to thwart the popular will. "The hopes of the imperialist triangle (America, UK and the Zionist regime) for a crawling coup d'etat in the Middle East and revival of the dead Middle East plan have been dashed," it declared.

Javan newspaper was similarly acerbic. "Today democracy slogans have become a lever to provoke, interfere and overthrow," it said. "By announcing results in the presidential elections that did not benefit their favourite candidate ... some foreign media such as BBC Persian [service], al-Arabiya, Fox News, CNN and some French media have started a new wave to create social and political division and cause riots."

In largely cautious responses to Friday's polls, Barack Obama's administration has been careful not to feed the fires of xenophobic resentment. "It's up to Iranians to make decisions about who Iran's leaders will be. We respect Iran's sovereignty and want to avoid the US being the issue inside of Iran," Obama said. But Iranian officials say US protestations of non-interference would be more credible if the White House publicly cancelled a $400m Bush era covert programme, authorised in 2007, that they say was intended to destabilise Iran, with the ultimate aim of regime change.

According to the journalist Seymour Hersh, writing in the New Yorker last year, covert operations by the CIA and the Joint Special Operations Command were used to support the PJAK Kurdish dissident group in northern Iran, the disaffected ethnic Arab minority in Khuzestan, in the south-west, and militant Baluchi Sunni Muslim separatists in the south-east, bordering Pakistan.

While not officially acknowledged or disavowed in the US, the covert programme has been repeatedly linked by Iran to ongoing violence, bomb attacks and assassinations in all three areas, as well as to the main external opposition group, the Mojahedin-e-Khalq, which is allegedly funded and armed by the US. Iran also occasionally claims to have evidence of involvement by Israel's Mossad spy agency and British intelligence.

Although the problem can be overstated, Iranian leaders of all political complexions have reason to worry about the so-called minorities question in a country comprising multiple ethno-linguistic groups, namely Persians, Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Baluchis, Turkmen, Armenians, Assyrians, Jews and Georgians. Recent reports from Iranian Kurdistan, for example, speak of 100 or more checkpoints being erected by Revolutionary Guards and the shelling of PJAK positions inside northern Iraq.

Iranian officials linked the recent suicide bombing of a Shia mosque in Zahedan, in Sistan-Baluchistan, to US, British and Israeli support for the Jundullah Sunni Muslim separatist group. An unsuccessful attempt last month to blow up a domestic airliner in Ahvaz, in Arab Khuzestan, brought similar claims. Speaking after the Zahedan attack, the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei said: "No one can doubt that the hands of ... some interfering powers and their spying services are bloodied by the blood of the innocent."

Iran announced yesterday that members of a foreign-backed "anti-revolutionary group" responsible for fomenting unrest and armed with bomb-making materials had been arrested. Intelligence Minister Gholamhossein Mohseni-Ejei said the group "wanted to achieve its goal through explosions and terror and in this connection 50 people were arrested ... They were supported from outside the country."

Given the current uproar in Tehran, the temptation for leading regime figures such as Khamenei and Ahmadinejad to deflect attention by hitting out at real or imagined foreign enemies, for instance by indirectly re-targeting US forces in Iraq or causing problems for Nato forces in Afghanistan, is growing dangerously. But even such extreme measures may not work.

The moderate Seda-ye Edalat newspaper certainly wasn't swallowing the regime's line about external threats yesterday. "Why does the government not let the people protest peacefully?" it asked. "Why do we always want to call Iranian protesters a group of hooligans bribed by foreigners to sabotage everything?"

Todays zaman: South Azerbaijani hunger strikers continue to plead case globally

Five South Azerbaijani

politicians from northwestern Iran, imprisoned for establishing a

political party advocating their identity rights, are continuing a

hunger strike -- which has already turned critical for their health --

that they started in an effort to have their voices heard on the

international scene due to the failure of Iran's state-controlled media

to report on their situation.

The political activists have been on a hunger strike in the central prison in Tabriz since July 13 in protest of the sentence handed down against them. Relatives of the victims have confirmed that some of the activists have already been hospitalized because of the strike. According to the latest update from the prisoners' families on Sunday, visitations have been banned and the prisoners were transported on the eighth day of their hunger strike to a prison in Tehran without informing their families.

The imprisoned activists confirm that they will continue to strike until their prison sentence is canceled, which they say the court decided under the pressure of the Iranian intelligence community.

“Because of the Iranian media boycott on publishing news on Azeri nationalists, this [hunger strike] is an opportunity for us to make our voices heard internationally. This is just a stage in our struggle,” stated Duman Radmehr, brother of prisoner Shahram Radmehr.

Tabriz intelligence and the Tabriz prosecutor's office had demanded the most severe punishment for the prisoners, and it was given by the court. The prisoners were detained during a series of arrests that began in December last year in Iran, and they were sent to the central prison in Tabriz.

Yeni GAMOH has been active in abroad for years. The five imprisoned activists were on the administrative board of the party, under the chairmanship of Hassani.

Amnesty International issued a report on June 12 expressing worry for the situation of imprisoned activists in Iran, including those five from Yeni GAMOH.

Families of the prisoners have confirmed that the five activists were in solitary confinement and that they were tortured physically and mentally by Iranian intelligence officers before being sent to prison in March. Included in the unlawful treatment of the detainees were long periods of interrogation, severe beatings and days of solitary confinement. They were only permitted to get a lawyer almost five months after their detention and just one week before the court hearing, the families also said.

All of Iran's Azeri political groups had to organize outside the country because the Azerbaijani population is not a “recognized minority” in the country. Article 26 of the Iranian constitution only allows “[the] formation of parties, societies, political or professional associations, as well as religious societies, whether Islamic or pertaining to one of the recognized religious minorities.”

Karim Asghari, an active South Azerbaijani activist, told Today's Zaman: “Iran could not accept that an Azeri political party, which it accused of having foreign/external origins, was found to be operating inside the country. [Yeni GAMOH] has declared that it wants transparent politics, which has been lacking in Iran for many years.”

‘New presidency won't decrease pressure on South Azerbaijanis

South Azerbaijanis think that the changing presidency in Iran due to the June elections will not improve their situation, although the president-elect, Hasan Rohani, is a moderate conservative supported by Iranian democrats. His election has been read as a signal of a more moderate Iranian policy, both vis-à-vis domestic actors and foreign relations.

South Azerbaijanis are not so optimistic about Rohani abiding by his promise to them before the elections on allowing education in their mother tongue. “After the elections, he [Rohani] has returned to the state's old discourse, saying ‘all of us are Persians, so no need for any other language,'” Asghari stated.

Shahin Helali Khyavi, a friend of the prisoners who is based outside Iran, however, estimated that such a harsh punishment would not have been made if the arrests and trials had not occurred during the last period of the outgoing President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, indicating his hope for Rohani.

Iranian-Azeri people living in northern Iran define themselves as southern Azerbaijani Turks and are struggling with the Iranian regime as they have been denied their ethnic rights granted in Articles 15 and 19 of the Iranian constitution, which provides for the equal treatment of all ethnic groups and freedom to use their mother tongue in media and education. However, these Azeri Turks in Iran have been arbitrarily deprived of such rights, while other ethnic groups, such as Armenians, enjoy their freedoms. Iran has an Armenian population of 200,000, while the number of ethnic Azerbaijanis in Iran amounts to 35 million.

amnesty: Iran: Halt Execution of Arab Minority Men. Four Ahwazi Arabs Sentenced to Hang After Unfair Trials

Document - Iran: Halt Execution of Arab Minority Men. Four Ahwazi Arabs Sentenced to Hang After Unfair Trials

JOINT PUBLIC STATEMENT

AI Index: MDE 13/031/2013

26 July 2013��Iran: Halt Execution of Arab Minority Men

Four Ahwazi Arabs Sentenced to Hang After Unfair Trials ��(London,

July 26, 2013) – Iran’s judiciary should stop the executions of four

members of Iran’s Ahwazi Arab minority because of grave violations of

due process, Amnesty International, the Iran Human Rights Documentation

Center, and Human Rights Watch said today. The judiciary should order a

new trial according to international fair trial standards in which the

death penalty is not an option. Family members and Ahwazi Arab rights

activists have told human rights groups that the detainees contacted

their families on July 16, 2013 and said they feared that authorities

were planning to carry out the execution orders any day now.

According to information gathered by the

rights groups, authorities kept the defendants, including three others

who have received unfair prison sentences, in incommunicado pretrial

detention for months. The authorities denied them access to a lawyer and

harassed and detained their family members. The trial suffered from

procedural irregularities and the convictions were based on

“confessions” that defendants said had been obtained by torture. There

is no record the trial court investigated their torture allegations.

“The absence of lawyers at key stages in the

proceedings and the credible allegations of coerced “confessions” cast

strong doubts on the legitimacy of the Ahwazi Arabs’ trial, let alone

the death sentences,” said Tamara Alrifai, Middle East advocacy director

at Human Rights Watch. “The fact that the government has an appalling

rights record against Iran’s Ahwazi Arab minority only makes the case

for the need for a fair trial stronger.”

The court sentenced Ghazi Abbasi, Abdul-Reza

Amir-Khanafereh, Abdul-Amir Mojaddami, and Jasim Moghaddam Payam to

death for the vaguely-defined “crimes” of moharebeh (“enmity against God”) and ifsad fil-arz

(“corruption on earth”). These charges related to a series of shootings

that allegedly led to the death of a police officer and a soldier. The

court sentenced three other defendants --Shahab Abbasi, Sami

Jadmavinejad, and Hadi Albokhanfarnejad -- to three years in prison in

the northwestern city of Ardebil for lower-level involvement in the

shootings. The lower court issued its judgment a week after a trial that

lasted approximately two hours, said letters to Ahwazi Arab rights

groups allegedly written by the defendants.

Security and intelligence forces have

targeted Arab activists since April 2005 after reports that Iran’s

government planned to disperse Ahwazi Arabs from the area and to attempt

to make them to lose their identity as Ahwazi Arabs.

The Iranian authorities have executed dozens

of people since the disputed 2009 presidential election, many of them

from ethnic minorities, for alleged ties to armed or “terrorist” groups.

Following unrest in Khuzestan in April 2011, the human rights groups

received unconfirmed reports of up to nine executions of members of the

Arab minority. In June 2012, a further four were executed and reports

suggest that five were executed in April 2013.

Branch 1 of the Revolutionary Court of Ahvaz, the capital of

Khuzestan province, issued the sentences on August 15, 2012. Branch 32

of Iran’s Supreme Court affirmed the sentences in February 2013.

Revolutionary courts are authorized to try cases classified by the

judiciary as pertinent to political and national security matters. Their

trials take place behind closed doors, and revolutionary court

prosecutors and judges are allowed, under longstanding legislation,

extraordinary discretionary powers, especially during the pretrial

investigation phase, to limit or effectively prevent the involvement of

defense lawyers.

The revolutionary court’s judgment, a copy

of which the human rights groups reviewed, said the court convicted the

seven men for the vaguely-defined “crimes” of moharebeh (“enmity against God”) and ifsad fil-arz

(“corruption on earth”). The court found that the defendants had

established a “separatist ethnic” group that “used weapons and engaged

in shooting in order to create fear and panic and disrupt public

security.”

None of the defendants had a prior criminal

record, the judgment says. All seven are residents of Shadegan (also

known as Fallahiya in Arabic), approximately 100 kilometers south of

Ahvaz.

In several of the letters, the writers said

that security and intelligence forces had held the seven men in

incommunicado detention for months, subjected them and their family

members to detention and ill-treatment to secure “confessions”, and

tried them simultaneously in one session that lasted less than two

hours. The letters said that none of the six lawyers present had an

opportunity to present an adequate defense of their clients.

In one letter, the defendant alleges that

despite the lack of evidence, intelligence agents pressed the

revolutionary court to convict the men of moharebeh and ifsad fil-arz

and to sentence them to death. In another letter, the defendants allege

that none were questioned during pretrial interrogations about the

supposed armed group – Kita’eb Al-Ahrar to which authorities say they

belong, even though their alleged membership was used by the judiciary

as the basis for their death sentences.

In a defense pleading criticizing the lower

court’s ruling, a copy of which the rights groups reviewed, one of the

lawyers criticizes the lower court’s ruling on several grounds,

including the court’s failure to look into the defendants’ allegations

that their “confessions” were extracted under torture.

The rights groups could not independently verify the authenticity of the letters or the defense pleading.

A former detainee who spoke to the human

rights groups on condition of anonymity said that for about two weeks in

2011 he was in the same ward of Karun prison as the four men sentenced

to death. He said that both Amir-Khanafereh and Ghazi Abbasi told him

that during their time at the Intelligence Ministry detention facility

in Ahvaz agents blindfolded them, strapped them to a bed on their

stomachs, and beat them with cables on their backs and feet to get them

to confess to using firearms.

The source also said that he observed

black marks around the legs and ankles of Amir-Khanafereh and Abbasi,

and that the two said the marks were caused by an electric shock device

used at the Intelligence Ministry detention facility. The source said he

had seen similar black marks on the legs of other Arab activists during

his time in Karun prison. The former detainee said that Amir-Khanafereh

and Abbasi told him that they were not allowed any visits and were held

incommunicado by Intelligence Ministry officials for months.

�The judgment, which primarily relied on the

alleged “confessions” of the defendants and circumstantial evidence,

stated that the members of this group were involved, among other things,

in several shootings at police officers and their property, and that

the shootings led to the deaths of at least two officers.

The Supreme Court judgment, a copy of which

the rights groups reviewed, affirmed the lower court’s ruling and

identified the victims as a police officer, Behrouz Taghavi, shot and

killed in front of a bank on February 26, 2009, and Habib Jadhani, a

conscripted soldier, who was shot and killed in spring 2008. Both the

lower court and Supreme Court judgements acknowledge that some of the

defendants retracted their confessions at trial saying they were

extracted under physical and psychological torture, but refused to

acknowledge the validity of those retractions. There is no record of any

investigation by either court into the allegations of torture.

Under articles 183 and 190-91

of Iran’s penal code, anyone found to have used “weapons to cause

terror and fear or breach public security and freedom” may be convicted

of moharebeh or ifsad fil-arz. Punishment for these charges includes execution by hanging.

“Considering putting to death the four

Ahwazis after a fundamentally flawed trial during which basic safeguards

such as rights of defense were blatantly disregarded and allegations of

torture and ill-treatment dismissed is abhorrent, said Hassiba Hadj

Sahraoui, deputy director of Amnesty International’s Middle East and

North Africa Program. “At the very least, the defendants should be

granted a new trial and the ability to properly defend themselves in

court. Anything less would risk that these men be executed for a crime

they may very well have not committed.”

The ICCPR fair trial provisions also require Iran to guarantee that all defendants should have adequate time and facilities to prepare their defense and to communicate with counsel of their own choosing. The UN Human Rights Committee has said that: “In cases of trials leading to the imposition of the death penalty scrupulous respect of the guarantees of fair trial is particularly important.”��Since June 14, the date of the recent presidential and local elections, unofficial and official sources have reported at least 71 executions. In 2012 Iran was one of the world’s foremost executioners, with more than 500 prisoners hanged either in prisons or in public.

“Four men are facing the gallows after a judge brushed aside their statement that their confessions were coerced,” said Gissou Nia, Executive Director of the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center. “At the very least, they deserve a fair trial and an impartial investigation of the abuse they say was used to force them to confess.”

�For more Human Rights Watch reporting on Iran, please visit:�http://www.hrw.org/en/middle-eastn-africa/iran�

For more Amnesty International reporting on Iran, please visit:

http://amnesty.org/en/region/iran

�For more information, please contact:

�In London, for Amnesty International, Sara Hashash (English, Arabic): +447831640170 or +44-20-7413-5566; or press@amnesty.org and Drewery Dyke (English, French, Persian) +447535587297; or ddyke@amnesty.org

In New Haven, for the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, Gissou Nia (English, Persian): _+1 203 772 2218; +1 203 654 9342 (mobile); or gnia@iranhrdc.org

�In New York, for Human Rights Watch, Faraz Sanei (English, Persian): +1-212-216-1290; or +1-310-428-0153 (mobile); or saneif@hrw.org

�In New York, for Human Rights Watch, Tamara Alrifai (English, Arabic, French, Spanish): +1-646-309-8896 (mobile); or alrifat@hrw.org

�In Beirut, for Human Rights Watch, Nadim Houry (English, Arabic, French): +961-3-639244; or houryn@hrw.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)