(CNN) -- In March 2009, when I was detained in Evin Prison in Iran, two evangelical Christians were arrested. I never met them but spotted them a few times through the barred window of my cell as they walked back and forth to the bathroom down the hall.

I would later learn that Maryam Rostampour and Marzieh Amirizadeh had converted from Islam to Christianity and faced charges of spreading propaganda against the Islamic Republic, insulting religious sanctities, and committing apostasy. They resisted severe pressure to renounce their faith, and in November 2009, after an international outcry, the two women went free.

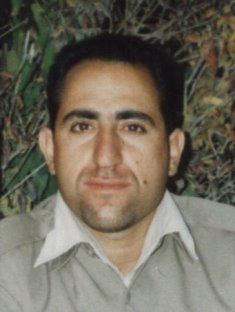

News headlines are now highlighting the plight of another Iranian Christian accused of apostasy, or abandoning one's religion. When Pastor Youcef Nadarkhani was 19, he converted from Islam to Christianity. In 2010, a provincial court sentenced him to death. This year, Iran's Supreme Court ruled that the case should be reviewed and the sentence overturned if he recants his faith -- a step Nadarkhani, 34, has so far refused to take.

Now, according to the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, Iran's judiciary has ordered the verdict to be delayed, possibly for one year. But Nadarkhani's supporters hope sustained worldwide pressure will lead to his just and immediate release.

As international criticism has mounted, an Iranian official has alleged that Nadarkhani is being prosecuted not for his faith but for crimes including rape and extortion. Nadarkhani's attorney, however, says the only charge the pastor has faced is apostasy, and court documents support this assertion.

Although Iran's penal code does not include a specific provision for apostasy, judges are given a fairly wide degree of latitude to issue rulings based on their own interpretation of Islamic law. In the past this has led to punishments ranging from imprisonment to death. The last person officially executed in Iran for apostasy was Hossein Soodmand, a Pentecostal minister who converted from Islam before Iran's 1979 Islamic Revolution and was hanged in 1990.

Iranian officials often say their country's recognized religious minorities (Christians, Jews, and adherents of the ancient Persian religion of Zoroastrianism) enjoy freedoms equal to their Muslim counterparts. Iran's constitution gives these three religious minorities certain rights, such as five seats in the 290-member parliament and the freedom to perform their religious rituals.

The constitution's articles, however, are all set within the boundaries of Islam, and Islamic codes grant superior legal status to male Muslims.

Many non-Shiites in Iran have also complained of limits on education, work, and exercising their faith. Critics accuse the Islamic regime of having monitored, harassed, abducted, detained, tortured, and killed citizens based upon their religion. Since 1999, the U.S. State Department has designated Iran a "country of particular concern" because of religious repression. The State Department has focused on the treatment of Sufi and Sunni Muslims, Protestant evangelical Christians, Jews, Shiites who don't share the government's official views, and Baha'is, whose faith is not recognized by Iran's regime.

Christian leaders in Iran have usually blunted their criticism of the regime, in part to avoid tensions. When I attended Christmas Eve Mass in Iran four years ago, I saw a few dozen worshipers, but I also heard that they had to get government permission to hold the service and were not allowed to proselytize. They had a Christian school, but it had to have a Muslim principal. They could print Christian texts but only with the authorities' approval.

A number of Iranian Christians who recently left Iran have told me that since the country's 2009 disputed presidential election, pressure on their communities has intensified, prompting many more Christians to emigrate. In April, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom reported a rise in Iranian authorities raiding church services and harassing worshipers.

Evangelicals and other Protestants have been particularly targeted. Unlike Iran's traditionally recognized Christian minorities, such as Armenians, Assyrians, and Chaldeans, evangelical churches hold their services in the Farsi language. Iranian authorities accuse them of spreading Christian writings in Farsi to convert Muslims.

"They are tough on us because we educate others," a former pastor of an underground evangelical church in Iran told me on condition of anonymity. "They call it proselytizing, but we don't proselytize. We discuss the realities that Jesus Christ talks about in the Bible, and we never speak about the Islamic Republic."

Shortly after their release from prison, Maryam and Marzieh, the two Christian converts detained down the corridor from me, left Iran. If they stayed, they may have shared the tragic fate of the Rev. Mehdi Dibaj.

Dibaj, a Christian convert from Islam, was jailed for a decade and released in 1994 after international appeals. Soon afterward, he went missing. The authorities reported the discovery of his corpse in a wooded area west of Tehran. Iran's government blamed an anti-regime group for the murder.

If the Iranian regime wants to tout religious freedom, it should respect its citizens' right to decide one of life's most personal choices: their spiritual path. A regime that claims to observe human rights and base its actions on the peaceful nature of Islam should also explain how peace would be attained by executing a man whose only crime is his faith.

By releasing Youcef Nadarkhani before Christmas, Tehran would take an important step toward respect for human rights and would give his wife and children an unforgettable gift.

No comments:

Post a Comment