Sunday 9 May 2010

The living conditions of Iran’s Arab population

By Loghman Ahmadi

March 11, 2010, 8:51 am

At the same time as the Islamic Republic of Iran sends millions of dollars to extremist Arab organizations in Lebanon, Palestine and Iraq the Arab population of Ahwaz in Iran suffers extreme poverty and discrimination.

The Islamic Republic of Iran portrays its self as the champion of Arab rights in all of the above-mentioned countries, but the Arab population of Iran faces discrimination and violence in all spheres of life. Every year hundreds of Arab-rights activists are imprisoned, tortured, raped and executed in Iran just because they raise their voices about the gross living conditions of Arabs in Iran.

The province of Khuzestan, which has an Arab majority, produces the majority of Iran’s oil, but none of the benefits of the oil reach the people living in the region. The Islamic Republic of Iran drains Khuzestan of its riches and systematically oppresses the Arab population, only to send its oil profits to Arab-extremists in other parts of the region.

This kind of policy is expected from the regime in Tehran, but what strikes Arabs in Iran as strange is that no Arab country or organization raises their plight or objects to Iran’s treatment of their kinsmen.

March 11, 2010, 8:51 am

At the same time as the Islamic Republic of Iran sends millions of dollars to extremist Arab organizations in Lebanon, Palestine and Iraq the Arab population of Ahwaz in Iran suffers extreme poverty and discrimination.

The Islamic Republic of Iran portrays its self as the champion of Arab rights in all of the above-mentioned countries, but the Arab population of Iran faces discrimination and violence in all spheres of life. Every year hundreds of Arab-rights activists are imprisoned, tortured, raped and executed in Iran just because they raise their voices about the gross living conditions of Arabs in Iran.

The province of Khuzestan, which has an Arab majority, produces the majority of Iran’s oil, but none of the benefits of the oil reach the people living in the region. The Islamic Republic of Iran drains Khuzestan of its riches and systematically oppresses the Arab population, only to send its oil profits to Arab-extremists in other parts of the region.

This kind of policy is expected from the regime in Tehran, but what strikes Arabs in Iran as strange is that no Arab country or organization raises their plight or objects to Iran’s treatment of their kinsmen.

BBC: Azeris feel Iranian pressure

Members of Iran's Azeri minority have long complained that their rights are stifled. They make up a quarter of Iran's population, but claim the authorities are worried about an uprising by ethnic Azeris, as Tom Esslemont reports from the Azerbaijan-Iran border.

By 0900 the border between Azerbaijan and Iran is jammed.

Dozens of Azeri men and women with large plastic bags jostle to squeeze through a grey metal gate to passport control - and beyond that, Iran.

Dozens of Azeri men and women with large plastic bags jostle to squeeze through a grey metal gate to passport control - and beyond that, Iran.

Border guards shout at them in an attempt to keep them in line. It fails.

For decades Azeris have crossed this fluid border to see family and friends on the other side.

For decades Azeris have crossed this fluid border to see family and friends on the other side.

Iran has a sizeable ethnic Azeri minority and many well-known Iranian politicians and public figures past and present have Azeri roots.

The territory we now know as modern-day Azerbaijan was once part of the Persian Empire, but was ceded to Tsarist Russia in the 19th Century.

Azeris on both sides of the border share a common language and cultural heritage. There have been Turkic-speakers living on both sides of the Araxes river, which now forms the border, for more than 700 years.

Azeris on both sides of the border share a common language and cultural heritage. There have been Turkic-speakers living on both sides of the Araxes river, which now forms the border, for more than 700 years.

On the run

These days the existence of a border between the two Azeri-dominated lands is just taken for granted.

These days the existence of a border between the two Azeri-dominated lands is just taken for granted.

"I go to market on the other side because the food is cheaper there," says Gulchohra Hasanova as she emerges through the border gate, her shopping basket laden with nuts and fruit.

She had returned from Iran with enough food to last her a few days. Hers is a story echoed by dozens who cross back and forth on a daily basis in the border town of Astara.

Iranians also come here to buy alcohol - the sale of which is banned in their country. But the freedom of movement is not open to everyone.

Not far away in his damp, dark two-room apartment I meet Mohammad Rza Lavai, an Iranian Azeri.

Not far away in his damp, dark two-room apartment I meet Mohammad Rza Lavai, an Iranian Azeri.

As he tries to light the gas stove in his kitchen he tells me he is on the run.

He says he fled Iran in September, claiming he had been persecuted for his ethnicity.

He says he fled Iran in September, claiming he had been persecuted for his ethnicity.

He shows me articles he wrote while he was there - printed in Azeri newspapers - in which he criticizes the Iranian government for their "treatment of the Azeris".

"They did not like it when I used to write in Azeri and publish my work in newspapers: I strongly criticised the regime," he says.

"They did not like it when I used to write in Azeri and publish my work in newspapers: I strongly criticised the regime," he says.

"Soon the authorities called me in. I was jailed several times."

He is visibly shaken and points out that he is now on medication.

"In jail I was electrocuted and beaten," he continues. "There is no such thing as human rights in Iran."

He is visibly shaken and points out that he is now on medication.

"In jail I was electrocuted and beaten," he continues. "There is no such thing as human rights in Iran."

Awkward relationship

It is impossible to verify Mr Lavai's story, and the Iranian constitution does not ban Azeri - but I came across others with similar stories, who did not want to speak on record.

It is impossible to verify Mr Lavai's story, and the Iranian constitution does not ban Azeri - but I came across others with similar stories, who did not want to speak on record.

“ There's no doubt that Sahar TV is the voice box of the Iranian authorities ” Khagani Ibadov Azeri journalist

Many Azeris living in Iran often complain that their culture and language are restricted there.

Emin Huseynzade, Caucasus project manager at the think tank Transitions Online, says there has always been an awkward relationship between Azerbaijan and Iran.

"It started during the Shah period," he says. "And [it has become] a tradition: to keep Azeris out of education, out of the [Iranian] culture.

"People were not allowed to give their son or daughter an Azeri name. The cultural life in Iran pushed Azeris to become Persians. That is the main problem actually."

"People were not allowed to give their son or daughter an Azeri name. The cultural life in Iran pushed Azeris to become Persians. That is the main problem actually."

Professor Ali Ansari of St Andrew's University, an expert in Iranian history, says it is seen differently by the Iranian authorities.

"Azeri culture was suppressed in Iran but it has been tolerated and at times encouraged for political purposes," he says.

"Azeri culture was suppressed in Iran but it has been tolerated and at times encouraged for political purposes," he says.

"However the Iranians are understandably very sensitive to any murmur of separatism and will crack down quickly on this."

Anger through television

These days there is another problem, in that Azerbaijan now supplies Israel with much of its oil.

These days there is another problem, in that Azerbaijan now supplies Israel with much of its oil.

By way of a response, Iran appears to be showing its anger through television.

When you turn on a television set in southern Azerbaijan it is possible to pick up Iranian TV.

When you turn on a television set in southern Azerbaijan it is possible to pick up Iranian TV.

Sahar TV broadcasts in the Azeri language. Its programmes regularly contain criticism of Azeri policy.

Men watch Sahar in tea rooms in towns like Astara and nearby Lenkoran.

The television set is always on, though not necessarily tuned into Sahar all the time.

The television set is always on, though not necessarily tuned into Sahar all the time.

Many say they only watch it out of curiosity, calling it Iranian propaganda.

Azeri nationalism?

Azeri nationalism?

Azeri journalist Khagani Ibadov says: "There's no doubt that Sahar TV is the voice box of the Iranian authorities.

"The presenters often accuse Azerbaijan of being a Zionist regime because of our strong ties with Israel. It shows just how worried they are about Azeri nationalism."

Sahar TV has, on at least one occasion, doctored an image of the Azeri flag so that the crescent moon was replaced with the Star of David, I was told.

As Mr Ibadov warms his hands on his glass of hot green tea he tells me Sahar TV is state-controlled.

As Mr Ibadov warms his hands on his glass of hot green tea he tells me Sahar TV is state-controlled.

"The programme presenters say everything that the Iranian government is too afraid to say directly," he says.

Back at the border Azeris continue to cross freely into and out of Iran.

In spite of everything Iran and Azerbaijan do enjoy bilateral ties and last year their trade turnover was reported to be $700m (£450m).

In spite of everything Iran and Azerbaijan do enjoy bilateral ties and last year their trade turnover was reported to be $700m (£450m).

Lorries, emerging through thick soupy puddles that have collected at the border, carry Iranian produce, destined for local markets, the Azeri capital, Baku - and beyond.

The trade continues, but the stark differences between these two neighbours remain.

Foreign Policy Journal: Balochistan – The other side of the story

By Moign Khawaja

“I believe there will ultimately be a clash between the oppressed and those doing the oppressing. I believe that there will be a clash between those who want freedom, justice and equality for everyone and those who want to continue the system of exploitation. I believe that there will be that kind of clash, but I don’t think it will be based on the colour of the skin. You’re not to be so blind with patriotism that you can’t face reality. Wrong is wrong, no matter who does it or says it.” — Malcolm X

“I believe there will ultimately be a clash between the oppressed and those doing the oppressing. I believe that there will be a clash between those who want freedom, justice and equality for everyone and those who want to continue the system of exploitation. I believe that there will be that kind of clash, but I don’t think it will be based on the colour of the skin. You’re not to be so blind with patriotism that you can’t face reality. Wrong is wrong, no matter who does it or says it.” — Malcolm X

I’ve traveled across Pakistan several times. I’ve been to the plains of Punjab, the Indus valley, the foothills of Karakorum, the delta of Indus river and the coastal region of Makran. Every region has its attraction and charm but if one asks me honestly, Balochistan is by far the most interesting and fascinating region of Pakistan. Why? It is because the land of Balochistan is blessed with a spectacular terrain that includes mountains, deserts, plateau, sea, valleys, oases, and so much more.

It was my first trip to the region and I was traveling to Quetta to watch a highly charged football match between India and Pakistan. Like cricket, both arch rivals promise to deliver some thrilling sporting moments in football competitions as well. Anyway, I boarded the bus and headed to the provincial capital Quetta from Pakistan’s largest city Karachi.

It is very hard for me to hide my excitement and suppress my feelings. Sat in the bus I couldn’t help but smile and peek out from the window. Soon I noticed that a young guy came to my seat and asked to sit next to me which I did not mind. After formal introduction he asked if I was a foreigner traveling to Balochistan for the first time. “I hope you don’t have preconceived ideas about our nation Mr. Khawaja,” he said in a sarcastic tone. “I believe in my own observations and forming my own opinion based on them,” came my reply with a smile to which he seemed much relieved.

It is very hard for me to hide my excitement and suppress my feelings. Sat in the bus I couldn’t help but smile and peek out from the window. Soon I noticed that a young guy came to my seat and asked to sit next to me which I did not mind. After formal introduction he asked if I was a foreigner traveling to Balochistan for the first time. “I hope you don’t have preconceived ideas about our nation Mr. Khawaja,” he said in a sarcastic tone. “I believe in my own observations and forming my own opinion based on them,” came my reply with a smile to which he seemed much relieved.

Azizullah was a 23 year old student who was studying medicine at a university in Karachi. Appearing to be a very quiet and reserved young man, he later became more friendly and chatty. He came from a middle class Baloch family from Khuzdar area in central Balochistan. “My father and uncles are doctors as well but I wanted to break the tradition of our family and become a diplomat,” he lamented as we started the conversation. The driver set off to Quetta at the same time.

CONUNDRUM

As our chat progressed he went on to tell me how hard it is to become a diplomat due to his ethnic background. Soon my Baloch friend lobbed this conundrum at me: “Guess a land that is blessed with natural wealth yet suffers from chronic poverty. A civilization that is rich of culture and traditions yet suffers from degradation. A nation that takes pride in its values and traditions yet suffers from suppression of identity. A laborer that works hard with patience and diligence yet gets exploitation and oppression as wages. And ironically, a cow that is forced to give milk yet starves for fodder to survive.” I resorted to scratching my head and wondered what I’m about to learn from him…

Balochistan has been in the news over the past few years due to the low level insurgency going on in the region.

Balochistan has been in the news over the past few years due to the low level insurgency going on in the region.

Thousands of activists are actively fighting the authorities in the volatile provinces of Balochistan in Pakistan and in Sistaan va Balochistan province in neighboring Iran. Many people in both Pakistan and Iran insist that foreign powers are actively meddling in the state of affairs of these provinces and are bent upon breaking them away from the nation. One can find both Iranian and Pakistani analysts filling hundreds of pages of newsprint with information on how the Baloch fighters are getting weapons from U.S.A. and other regional powers. However, one thing you’ll seldom find them telling is the reason why some Baloch ‘miscreants’ have taken weapons in their hands and are waging a war for autonomy or independence.

I wasted no time and asked Azizullah the same question. “It is convenient to label someone a criminal or terrorist. A person commits a crime and he becomes a criminal. A kidnapping, shooting, killing, assassination or bombing and a terrorist is born,” the medical student expressed philosophically. After a brief pause while reading my facial expressions, he continued: “However, seldom we come to know what the motives were behind every criminal or terrorists’ action. It is not possible to believe that all these people are born evil and their only purpose of life is to bring destruction and harm to the society. So what is the rationale?” Azizullah’s questions started to become intense and critical.

LAND, PEOPLE AND PRIDE

Balochistan is a region that is spread across Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan. The combined area of this region is around 600,000 square kilometers, which is about the size of Ukraine; 347,000 km² is part of Pakistan, 181,785 km² in Iran and around 70,000 km² in Afghanistan. Despite having large areas in Pakistan and Iran, the Baloch population is around 5 million and 2 million respectively in both the countries. It is estimated that more than 200,000 Baloch people live in southern Afghanistan.

According to contemporary Baloch scholar Dr. Naseer Dashti, Baloch people trace their history to the ancient Parthian family of Aryan tribes living in the Caspian Sea region. The Baloch tribes began to settle in to present day Balochistan as early as 1200 AD. The migration of Baloch population from Caspian Sea region to the present semi-desert land of Balochistan took place in three different times and places.

Balochistan is a region that is spread across Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan. The combined area of this region is around 600,000 square kilometers, which is about the size of Ukraine; 347,000 km² is part of Pakistan, 181,785 km² in Iran and around 70,000 km² in Afghanistan. Despite having large areas in Pakistan and Iran, the Baloch population is around 5 million and 2 million respectively in both the countries. It is estimated that more than 200,000 Baloch people live in southern Afghanistan.

According to contemporary Baloch scholar Dr. Naseer Dashti, Baloch people trace their history to the ancient Parthian family of Aryan tribes living in the Caspian Sea region. The Baloch tribes began to settle in to present day Balochistan as early as 1200 AD. The migration of Baloch population from Caspian Sea region to the present semi-desert land of Balochistan took place in three different times and places.

Baloch tribes first migrated to present day Balochistan from the northern areas of Mesopotamia, what is now called Kurdistan. These Baloch are known as Narui (Nara denoting north in archaic Balochi language). They settled in the area of Sistan in present-day Iran, Helmand valley in southern Afghanistan and Chagai plains in present Pakistani province of Balochistan.

Historic map of the region.

The second migration followed the first after a few hundred years. The incoming Baloch tribes moved from Mount Elburz in the south of Caspian Sea and settled in central Balochistan areas of Khuzdar and Kalat in Pakistan.

The Baloch intellectual adds that the third and most important of all is the migration of the remaining Baloch tribes said to be living in Syrian city of Aleppo who first settled in Kerman (present day Iran), then Makran and finally in the plains of Sibi and Kachchi in eastern Balochistan. This migration took place during 12th century AD.

Historic map of the region.

The second migration followed the first after a few hundred years. The incoming Baloch tribes moved from Mount Elburz in the south of Caspian Sea and settled in central Balochistan areas of Khuzdar and Kalat in Pakistan.

The Baloch intellectual adds that the third and most important of all is the migration of the remaining Baloch tribes said to be living in Syrian city of Aleppo who first settled in Kerman (present day Iran), then Makran and finally in the plains of Sibi and Kachchi in eastern Balochistan. This migration took place during 12th century AD.

While I read the above mentioned information in notes given by Azizullah, he answered a call on his mobile phone. Hearing Balochi language for the first time I tried to understand a few words that are used in both Urdu and Arabic.

“Balochi is the language spoken by the Baloch people. It is a member of the Indo-Aryan languages,” he explained after sensing my curiosity about his language. “Balochi is closely related to Kurdish, Persian and Sanskrit languages but it is believed to be more ancient than these languages. We also carry a heavy influence of Arabic due to the Islamic conquests in the region during the middle age.” I was left pleasantly surprised that our languages had so many things in common including the use of same Arabic script.

While the bus moved at a high speed thanks to the recent improvements on the RCD Highway, I began grilling my friend about Baloch history and the immense pride attached to it. His answers were immediate.

“Baloch people have historically defended themselves from foreign invaders by forming loose tribal unions. The unions are linked through trade, agriculture and livestock. This cooperation helped them interact socially, politically and militarily, in case of invasions,” the young medical student explained succinctly. It was obvious that he was enjoying this conversation and knew about the history of his nation very well.

“Balochi is the language spoken by the Baloch people. It is a member of the Indo-Aryan languages,” he explained after sensing my curiosity about his language. “Balochi is closely related to Kurdish, Persian and Sanskrit languages but it is believed to be more ancient than these languages. We also carry a heavy influence of Arabic due to the Islamic conquests in the region during the middle age.” I was left pleasantly surprised that our languages had so many things in common including the use of same Arabic script.

While the bus moved at a high speed thanks to the recent improvements on the RCD Highway, I began grilling my friend about Baloch history and the immense pride attached to it. His answers were immediate.

“Baloch people have historically defended themselves from foreign invaders by forming loose tribal unions. The unions are linked through trade, agriculture and livestock. This cooperation helped them interact socially, politically and militarily, in case of invasions,” the young medical student explained succinctly. It was obvious that he was enjoying this conversation and knew about the history of his nation very well.

“Balochistan’s geo-political location meant it was never safe from external threats or interventions, however, the combined threat of tribal unions enabled them to ward off Persian, Afghan and other influences,” he added with a hint of bitterness in his tone.

POLITICS OF PROMISES

We travelled around 200 kms during the last two and a half hours and stopped for refueling and refreshments. My travel mate bought me a delicious fruit cake and tea as we sat on charpoy – a traditional bed consisting of wooden frame and woven ropes.

We travelled around 200 kms during the last two and a half hours and stopped for refueling and refreshments. My travel mate bought me a delicious fruit cake and tea as we sat on charpoy – a traditional bed consisting of wooden frame and woven ropes.

“If you count the promises made to us, we must be the richest people in the world,” Azizullah’s rant continued. “Take this highway for example. Back in 1980s, Iran, Turkey and Pakistan decided to link their countries through a highway which they named RCD. Starting from Istanbul, it crisscrossed Turkey, Iran and was supposed to end in Karachi. While Turkey and Iran completed their part of the highway, Pakistani project languished for years. Only Gen. Musharraf took interest in the project and got it completed finally.”

I was surprised to hear Azizullah, an ethnic Baloch, praising for Gen. Musharraf, the former military dictator of Pakistan who ruled the country from 1999 to 2008. However, his praise soon turned into criticism when I asked about his role in Balochistan’s society.

He dragged me to a nearby petrol station. “This is part of Pakistan, right?” He poked a question to which I nodded in affirmation. “Well, the only thing we use here is the Pakistani currency. Apart from that everything else is smuggled from Iran. Fuel, food, cosmetics, chemicals, crops, stationary, and even cars come from there,” Azizullah revealed while adding, “Fuel is dirt cheap. The Iranian fuel costs pennies if compared to the price we pay for branded Pakistani one. Not even fools will buy for that price.”

Most of Balochistan’s landscape is dominated by mountains with villages dotted across the region. (Photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

Most of Balochistan’s landscape is dominated by mountains with villages dotted across the region. (Photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

Azizullah blamed heavy duties that made Pakistani goods expensive and scarce. The Iranian goods, on the other hand, were cheap and easily available. Many people would argue that transporting goods to Balochistan is an expensive operation in terms of logistics and supply, however, the Baloch student argued that many industries can be opened in the province to give a boost to local industries, hence ending shortages and smuggling.

DEEP MISTRUST

It is hard to take people’s accounts by face value in a country where every person has different views from the others based on their perception of history, current affairs and politics. Aware of what Azizullah views can be conceived as grievances, they can also be seen as lame excuses and propaganda by people elsewhere.

It is hard to take people’s accounts by face value in a country where every person has different views from the others based on their perception of history, current affairs and politics. Aware of what Azizullah views can be conceived as grievances, they can also be seen as lame excuses and propaganda by people elsewhere.

“Azizullah, tell me honestly if you’re not against the tribal chiefs of Balochistan who don’t want to see their subjects getting literate and breaking the shackles of economic deprivation and political isolation,” I came forward with a question to clear the mist. He looked deep into my eyes before giving an answer.

“Moign, you asked me a typical question that is dipped into what I call ‘establishment’s propaganda’. Not a single Baloch on our land is against literacy and development. We know for a fact that the only way forward is to embrace science and technology,” the 23 year old said in an assuring tone.”We want to become part of the modern world. We have to exploit our natural resources for common good. However, all these plans made by our masters are deceptive as we are not part of them and they are not bound to benefit us.” Cynicism was back on his face.

“Moign, you asked me a typical question that is dipped into what I call ‘establishment’s propaganda’. Not a single Baloch on our land is against literacy and development. We know for a fact that the only way forward is to embrace science and technology,” the 23 year old said in an assuring tone.”We want to become part of the modern world. We have to exploit our natural resources for common good. However, all these plans made by our masters are deceptive as we are not part of them and they are not bound to benefit us.” Cynicism was back on his face.

Read any newspaper or watch any mainstream Pakistani news channel and you’ll find out that Balochistan is languishing due to its tribal structure and archaic sense of nationalism. “The people cry the old tale of exploitation yet never take the socio-economic opportunities given to them by governments,” is what you’ll hear retired army servicemen, economists, bureaucrats, politicians and religious leaders claiming in TV talk shows; loathing the Sardars (Baloch tribal leaders) and asking the Balochs to help the Pakistani army clean up their mess once and for all.

View of Gwadar deep sea port built with Chinese cooperation. (Photo: Wikimedia commons)

“They talk about highways, ports, cities, industries whereas we talk about education, health, jobs, opportunities for indigenous people. Our demands are down-to-earth whereas their promises are tall. We don’t see a match in their words and actions. We sense injustice, exploitation and colonization in the statements made by these pseudo-intellectuals,” Azizullah said referring to the analysts in Pakistani media.

View of Gwadar deep sea port built with Chinese cooperation. (Photo: Wikimedia commons)

“They talk about highways, ports, cities, industries whereas we talk about education, health, jobs, opportunities for indigenous people. Our demands are down-to-earth whereas their promises are tall. We don’t see a match in their words and actions. We sense injustice, exploitation and colonization in the statements made by these pseudo-intellectuals,” Azizullah said referring to the analysts in Pakistani media.

Azizullah’s views are not unique. They’re equally shared millions of Balochs living in Pakistani part of Balochistan. Poverty is widespread among Baloch nation and according to the UN Human Development Report, Balochistan stands lowest in human development index in the country. The province has a literacy rate of just around 27% compared to the national average of 47%. Around 1/3 of the total Balochistan population is unemployed or underemployed. Despite rich mineral resources, including coal, copper and natural gas, only 25% of Balochistan’s population receives electricity. Hardly 7% of the population of the province has access to sanitation and piped potable water.

ACCESSION OR OCCUPATION?

Facts clearly fuel Azizullah’s argument. They also provide ammo to the people who talk about separation of Balochistan from the federation of Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran and forming a new republic. After all, what have the Baloch achieved after they joined Pakistan in 1948? My young friend seized the opportunity to answer this question.

Facts clearly fuel Azizullah’s argument. They also provide ammo to the people who talk about separation of Balochistan from the federation of Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran and forming a new republic. After all, what have the Baloch achieved after they joined Pakistan in 1948? My young friend seized the opportunity to answer this question.

“My brother, please do not buy this notion that we joined Pakistan in 1948. Historically we never were part of British India. Our ruler, the Khan of Kalat, signed several treaties with the British that recognized his sovereignty in exchange of British protection. However, we stayed as a sovereign state outside India,” the medical student touched history once again and the conversation

started to flow in that direction.

Dr. Naseer Dashti is a respected Baloch scholar and activist who holds a PhD. on Baloch health-seeking behavior from the University of Greenwich. His two recently published books, ‘The Voice of Reason’ and ‘In a Baloch Perspective’ have been banned by Pakistani authorities. According to the Baloch nationalist, both British and Pakistanis accepted the sovereignty of Kalat state in a June 1947 partition plan. However, the British did not consult the Khan of Kalat over the transfer of leased Balochistan lands under British control. Consequently, British and Pakistani authorities held a controversial referendum in which their favored members took part and declared Balochistan as part of Pakistan.

Just before the creation of Pakistan, State of Kalat declared its independence on 12 August, 1947. However, this announcement was not welcomed by the new rulers of Pakistan and they started to force the Khan of Kalat to join the newly born Islamic republic. After their political advances were refused, Pakistani army marched into the Kalat territory on 26 March 1948 and forced the Khan to surrender his territory. The Khan of Kalat, though having no constitutional powers, agreed to sign the instrument of accession with Pakistan.

“History is not what you read in textbooks Mr. Khawaja,” Azizullah bounced back while I was reading his notes about Baloch history. “The accounts in Pakistani textbooks are all a peaceful and rosy affair when it comes to Balochistan,” he said with a sarcastic smile. “Reality is completely different.”

“History is not what you read in textbooks Mr. Khawaja,” Azizullah bounced back while I was reading his notes about Baloch history. “The accounts in Pakistani textbooks are all a peaceful and rosy affair when it comes to Balochistan,” he said with a sarcastic smile. “Reality is completely different.”

FRUSTRATION FUELS INSURGENCY

The journey was about to end as I was 5,500 feet above the sea level and entering Quetta valley. The views of the capital from surrounding mountains are just spectacular. It seems like you’re about to enter some saucer that is illuminated by glitter. I bid farewell to my friend and thanked him for such a productive discussion at the bus station. Finding out that I’m a football fan and came here just to watch the clash between Pakistan and India, he promised to join me in the stadium next day.

That evening I ventured into town and got a glimpse of the metropolis. I was struck by the level of cleanliness in the city. Unlike other Pakistani cities, I found Quetta remarkably clean and tidy. I returned to my hotel and turned on the TV. While flicking through the channels, I found a lively debate going on the TV. The participants were discussing the military operation waged by Pakistani army in Balochistan and some hot words were exchanged in due course.

That evening I ventured into town and got a glimpse of the metropolis. I was struck by the level of cleanliness in the city. Unlike other Pakistani cities, I found Quetta remarkably clean and tidy. I returned to my hotel and turned on the TV. While flicking through the channels, I found a lively debate going on the TV. The participants were discussing the military operation waged by Pakistani army in Balochistan and some hot words were exchanged in due course.

“The Sardars don’t like Gen. Musharraf’s pro-development policies and have taken up arms to destroy the project. They can’t see the profound impact of these development projects on Balochistan’s economy and fear losing their influence,” shouted one ex-military analyst. The nationalists opposing military presence in Balochistan and so-called ‘mega development projects‘ see it as part of colonizing their land.

“Who are you to give us anything? You give power to these sardars, you give them the government and when these very people don’t play according to your game plan you try to get rid of them,” yelled one Baloch activist in the discussion panel. “We don’t want you, your puppet Sardars (tribal leaders), your mega projects. Nothing. Leave our land and go back to the plains of Punjab,” the diatribe continued. The moderator, sensing the boiling tempers, called for a quick break. The program did not start again for a good 20 minutes. And when it did start, the compere apologized for lack of time and thanked his participants and called it a day.

Next day I was in the football stadium packed with spectators. I met Azizullah at the fixed place. The match eventually kicked off after formal pre-match ceremonies. While thousands of people were carrying green and white Pakistani flags, I saw some Indian supporters carrying the tri-color. Surprised, I quipped they must be Baloch separatists. My Baloch friend heard that with a broad smile on his face that I never saw before.

“Yes. They’re Baloch. They’re paid by the Indians to hoist their flag and cheer up the visitors. Something wrong with this? At least they’re not carrying guns and fighting the Pakistani army,” the Baloch student said with a thunderous laughter. I laughed too but took the joke with a pinch of salt.

“People love to gossip that Baloch rights movement is controlled by India. You’ll see Pakistani politicians and military generals making statements about New Delhi’s interference in Balochistan. They’ll claim India has hundreds of training camps here in our province. My simple questions: Where is the proof? Show me at least one camp where Indians are training the Baloch separatists. And even if there are camps, what the hell is the Pakistani establishment doing? How did they let the Indians infiltrate and establish their bases thousands of kilometers deep into Pakistani territory?”

Potent questions raised by Azizullah I thought. While I was thinking about the possible explanations, the restless soul continued his tirade. “They say India doesn’t like the Gwadar port as it will give Islamabad a new naval base. They also insist that this port will make us independent which the Indians won’t like at all. The Chinese have helped construct this port which displeases our ‘arch rival’.

Fishing boats moored outside the bay of Gwadar. (Photo: wetlandsofpakistan)

“Typical establishment rhetoric. I can understand that. But what I don’t understand is, how will this port make us prosperous while hardly 10% of the locals are employed by the port authorities?” the 23 year old medical student posed questions in an activist style. “Gwadar is a historic fishing port and Baloch people have been making a livelihood for centuries. This government seizes the town and declares it ‘federal territory’. They establish a cantonment, coast guard outposts and expel the poor fishermen from their waters and impose a 15 nautical mile curfew.

“Typical establishment rhetoric. I can understand that. But what I don’t understand is, how will this port make us prosperous while hardly 10% of the locals are employed by the port authorities?” the 23 year old medical student posed questions in an activist style. “Gwadar is a historic fishing port and Baloch people have been making a livelihood for centuries. This government seizes the town and declares it ‘federal territory’. They establish a cantonment, coast guard outposts and expel the poor fishermen from their waters and impose a 15 nautical mile curfew.

“And this is not the end. They give licenses to fishing trawlers from China and Far East to fish in our seas yet 80% of local population have no right to make a livelihood. Is this justice? You call this development or imperialism Mr. Journalist?”

It was hard for me to validate the figures provided by the young Baloch student. However, I got the gist of his arguments. History is rife with examples when indigenous people found themselves strangers in their own lands and were overran by invading settlers. The Native Americans vs European settlers; Incas vs Spanish; Aborigines vs White settlers; Uighurs/Tibetans vs Han Chinese; and Palestinians vs Israelis are just a few examples of colonialism and subsequent conflicts.

Balochs have long complained of being marginalized in their own lands. They blame Punjabis, the dominant ethnic group in Pakistan for their socio-economic exploitation that is going on for the last 60 years, whereas the Shia Iranians for their politico-religious suppression since the 1979 Khomeini revolution. Despite blessed with huge deposits of uranium, copper, gold, coal, natural gas, oil, sulfur and many other minerals, my three day stay in the province reminded me of some backward place of the world where clocks have lost their pace and time has become irrelevant.

Political propaganda aside, I saw no connections between Azizullah’s family with the feudal leaders. He was equally bitter about them as well. He blamed the government in Islamabad and its machinery for empowering the tribal chiefs instead of the people’s democracy. He vocally blasted the military operations and blamed them for disillusionment of the Baloch masses.

“They have cluster bombs, long range and anti-cave missiles to drop on our land yet they can’t build roads and reservoirs,” Azizullah continued to vent out his frustration. “Dams will enable our farmers to cultivate lands and increase agricultural output of the country.

“Fishing vessels and improved storage godowns will improve the livelihood of our fishermen and boost our exports. I’m not a separatist as I know battles come with a heavy cost but please tell me what choice is my nation left with? We’re forced to pay a heavy price for mega projects yet they’re not ready to provide us the very basic necessities like water, sanitation, education, gas and electricity, transport, jobs etc. I refuse to stay silent,” my young friend cried but didn’t speak any further.

The match ended in a 1-1 draw. Soon we headed to Quetta’s famous attraction, Lake Hannah, where we went for a boat ride. The mid-summer views were spectacular amidst the clear blue skies. My host’s mood was refreshed by the natural beauty around him and his temper seemed to ease a bit. I was ecstatic when he took me to a mountain top restaurant that is famous for its local dish called ‘Sajji’ – whole lamb stuffed with rice, roasted over burning coal.

While I was about to thank him for his hospitality and good company and say good bye, he asked me a quick question. “Agha (sir in Balochi language) Moign, I’ll ask one last question if you don’t mind,” to which I nodded with smile. “We had a boat trip at the lake, didn’t we. Say if I make you row the boat till the point of exhaustion, how will you react?”

The question puzzled me immediately. “Well,” I paused for a while. “I’ll resist and try to get rid of the captain who turned out to be my captor. If I can’t resist I’ll bore a hole in the ship so that he doesn’t get away with his crime and sink with me. You might think it is revenge but it will come out naturally,” I replied while trying to defend my actions.

“We, the Baloch people are doing the same my kind friend. We want to sail in the boat as equals but if we’re enslaved by the colonialists, we will not let this boat stay afloat.” he said in a firm tone. “We may be less in numbers but we live with our traditions and pride intact. For us, our homeland is more precious than our lives.” young Azizullah asserted.

Five years have passed since I first visited Balochistan. Things have not changed at all since then. The military operation continues and so does the insurgency mounted by Balochistan Liberation Army, a rag-tag militia of several Baloch tribes. Apart from the inauguration of a few mega projects and their topsy-turvy functioning, Balochistan stays more or less the most backward area of Pakistan.

During my visit, certain things dawned upon me. I was no more under the illusion that separatist movement is fueled by Washington, Tel Aviv or New Delhi and not the socio-economic grievances of the Baloch people. The uprising in western Pakistan and south-eastern Iran is a result of decades long systematic discrimination and exploitation by the governments in Tehran and Islamabad.

During my visit, certain things dawned upon me. I was no more under the illusion that separatist movement is fueled by Washington, Tel Aviv or New Delhi and not the socio-economic grievances of the Baloch people. The uprising in western Pakistan and south-eastern Iran is a result of decades long systematic discrimination and exploitation by the governments in Tehran and Islamabad.

Yes the tribal chiefs are to blame for the underdevelopment of Balochs. Yes they’re selfish and power hungry beasts but what about the excesses committed by security apparatus in Pakistan and Iran that is alienating the masses? Why do the Balochs remain the poorest in both the countries while living on one of the most richest lands in the world? Establishments in the Islamic Republics of Pakistan and Iran better answer these questions soon otherwise their boats stay at peril of getting sunk by the burden of greed, exploitation and expansion.

Loading... Moign Khawaja specialises in politics, current affairs and world conflicts. He also takes deep interest in society especially religious and cultural festivals. He has MA degrees in Journalism and International Affairs.

Loading... Moign Khawaja specialises in politics, current affairs and world conflicts. He also takes deep interest in society especially religious and cultural festivals. He has MA degrees in Journalism and International Affairs.

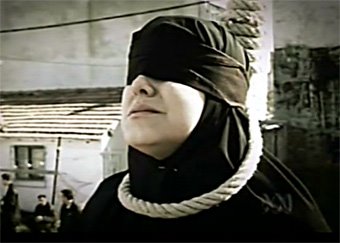

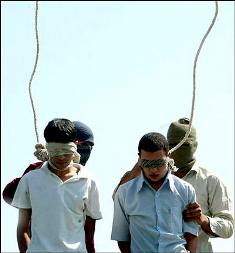

Irish Times: Iran hangs five Kurdish separatists

Iran hanged five members of a Kurdish group for various charges, including "moharebe" or waging war against God, the official IRNA news agency reported today.

The four men and one woman were members of the Party of Free Life of Kurdistan (PJAK), an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) which took up arms in 1984 for an ethnic homeland in southeast Turkey and northwest Iran."

The five … were hanged inside Tehran's Evin prison on Sunday morning ... They confessed carrying out deadly terrorist operations in the country in the past years," IRNA said.Iran sees PJAK, which seeks autonomy for Kurdish areas in Iran and shelters in Iraq's northeastern border provinces, as a terrorist group.

In recent years, Iranian forces have often clashed with PJAK guerrillas, who operate out of bases in northern Iraq. Kurds are large minorities in Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria.The five Kurdish activists were convicted in 2008.

They were hanged after a Supreme Court upheld their death sentences.IRNA said three of them were founders of PJAK group in Iran and were also involved in bombings that killed members of Iran's Revolutionary Guards, an elite force that is separate from Iran's regular armed forces.Four of the five were accused of involvement in a mosque bombing in the central city of Shiraz in 2008 which killed 14 people.

Like Iraq and Turkey, Iran has a large Kurdish minority, mainly living in the Islamic Republic's northwest and west. The United States in February 2009 also branded PJAK as a terrorist organisation.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)