Monday 30 August 2010

Reuters: U.N. urges Iran to tackle racism

Fri Aug 27, 2010 12:44pm GMT

GENEVA (Reuters) - Iran should do more to protect its ethnic minorities such as Arabs, Kurds and Baluch, a United Nations human rights body said on Friday.

The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), a group of 18 independent rights experts, said Iran lacked data on the numbers of ethnic minorities despite a census in 2007, but the participation of such people in public life appeared to be lower than could be expected.

Several armed groups opposed to the government are active in Iran, mostly made up of ethnic Kurds in the northwest, Baluch in the southeast and Arabs in the southwest.

"The Committee expresses concern at the limited enjoyment of political, economic, social and cultural rights by... Arab, Azeri, Balochi, Kurdish communities and some communities of non-citizens," it said in a report on a regular review of Iran's compliance with a 1969 international treaty banning racism.

The Committee also found discrimination is "rampant" against Baha'is -- a minority whose faith the Shi'ite govt considers a heretical offshoot of Islam -- committee member Dilip Lahiri said.

It also urged Iran to continue its efforts to empower women and promote their rights, paying particular attention to women belonging to ethnic minorities.

Some tenets of Islamic sharia law disadvantage Iranian women, Indian committee member Dilip Lahiri said. "On the other hand, in terms of their education and access to jobs, very remarkable progress has been made in Iran," he told a briefing.

The committee voiced concern at reports of a selection procedure for state officials and employees, known as "gozinesh," requiring them to demonstrate allegiance to the Islamic Republic of Iran and the state religion, which could limit opportunities for ethnic and religious minorities.

It said that lack of complaints was not proof of the absence of racial discrimination, as victims may not have confidence in the police or judicial authorities to handle them.

It called on Iran to set up an independent national human rights institution and report back to it at the start of 2013 on how it was dealing with the concerns and recommendations.

(For full report go to link.reuters.com/vyq67n )

(Reporting by Jonathan Lynn and Stephanie Nebehay; Editing by Charles Dick)

Saturday 21 August 2010

IMHRO condemn forcing Sakineh Ashtiani to confess on state TV

Iranian Minorities’ Human Rights Organisation (IMHRO)

Ref.IMHRO.78

21.08.2010

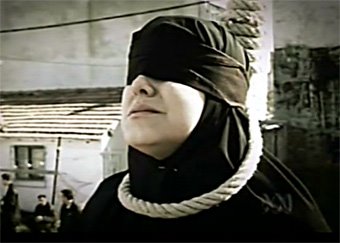

The Iranian government forced Sakineh Ashtiani to confess to murdering her husband and adultery on TV and have sentenced her to death by stoning. She pleaded guilty to these charges.

Her confession was broadcast on state TV in Iran just one week after her interview with The Guardian newspaper[i], where she said that authorities in Iran

Her lawyer, Mohammad Mostafaei, had to escape from Iran

IMHRO suggests that such confessions are all taken under torture and have no value at all. The Iranian government have broadcast many confessions since 1979 and we know that many are tortured.

IMHRO demands from the Iranian government the release of Sakineh Ashtiani, an Azeri woman, along with other Azeri prisoners. She already suffered inhumane punishment of ninety lashes; the injustice needs to be stopped now.

An interesting point is that she could not speak Farsi and her confession was in the language of Azeri, thus showing that Farsi is not a national language in Iran

Azeri, like Kurds, Arabs, Baluch and Turkmen, are forced to be educated in Farsi/Persian. Anyone speaking in their mother tongue could suffer disciplinary actions and even being sent to prison.

Background

Sakineh Ashtiani was an Azeri woman who was sentenced to death by stoning for murdering her husband and having a boyfriend, however, she denied the allegations.

Azeri is the largest ethnic group in Iran

Azeri is heavily suppressed by the Iranian security service. Azeri political parties’ are banned and political activists are tortured in prison. Many Azeri political activists are killed under torture.

Wednesday 11 August 2010

HRW: Iran: Free Baha'i Leaders

(New York) - The Iranian judiciary should set aside any judgments issued in closed judicial proceedings against seven Baha'i leaders and release them immediately given that no evidence appears to have ever been presented against them, and they have not been given a fair and public trial, Human Rights Watch said today.

The authorities arrested the seven in May 2008 and severely restricted their access to lawyers and their families. Government officials reportedly informed one of their lawyers in recent days that Branch 28 of the Revolutionary Court had sentenced each of the seven to 20 years in prison on charges that include propaganda against the state and espionage.

"For more than two years now the Iranian authorities have utterly failed to provide the slightest shred of evidence indicating any basis for detaining these seven Baha'i leaders, let alone sentencing them to 20 years in prison," said Joe Stork, deputy director of the Middle East division at Human Rights Watch.

The Baha'i faith originated in Iran in the 19th century and today has approximately 300,000 followers in that country. The Iranian government considers Baha'is to be apostates from Islam and bars them from openly practicing their faith. Baha'is face discrimination in higher education and many areas of employment. Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, security forces have arbitrarily arrested and detained hundreds of Baha'is on purported national security charges.

In the current case, security forces arrested six leaders of Iran's Baha'i community at their homes in Tehran on May 14, 2008. The six are Fariba Kamalabadi, Jamaloddin Khanjani, Afif Naeimi, Saeid Rezaie, Behrouz Tavakkoli, and Vahid Tizfahm. The authorities had arrested the seventh, Mahvash Sabet, the group's secretary, on May 5 in Mashhad, in northeast Iran, when he responded to a summons from the Intelligence Ministry.

After holding the seven in Evin Prison for 20 months without charge, on January 12, 2010, officials brought charges that included spying, "propaganda against the state," "collusion and collaboration for the purpose of endangering the national security," and "spreading corruption on earth." Authorities did not allow the five men and two women to post bail and allowed only limited visits from family members and lawyers. Their trial began January 12 and consisted of six brief closed-door hearings, the last on June 14.

Judge Mohammad Moghiseh conducted the trial at Branch 28 of the Revolutionary Court in Tehran. He also has presided over proceedings in the cases of numerous individuals unlawfully detained during peaceful protests against the results of the June 12, 2009 presidential election.

The United Nation's Office of the Baha'i International Community in Geneva reported that on August 9 authorities transferred the seven from Evin to Raja'i Shahr (also known as Gohardasht), a prison 20 kilometers west of Tehran. If true, this would suggest that they have been convicted and will serve their sentences in another prison.

Over the past two years, Human Rights Watch has repeatedly called on Iranian authorities to release the seven leaders due to government's inability or unwillingness to provide reasonable evidence warranting detention.

Government restrictions prevent Iranian Baha'is from openly practicing their faith or administering a National Spiritual Assembly, as they do in most other countries where Baha'i communities exist. Instead, Iran's Baha'is have formed an informal coordinating body known as the Friends of Iran. The seven who were detained are leaders and the secretary of this coordinating body.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Iran is a party, requires Iran to ensure that everyone facing a criminal charge has a "fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal" and that they have "adequate times and facilities for the preparation of their defence" and to communicate with the lawyer of their choosing.

During a review in February of its human rights record before the United Nations Human Rights Council, Mohammad Javad Larijani, the head of Iran's UN delegation, stated that "no Baha'i in Iran is prosecuted because he is a Baha'i," and the government rejected recommendations put forth by other governments calling for "an end to discrimination and incitement to hatred vis-à-vis the Baha'i."

"Iran should take concrete steps that show it is committed to protecting the fundamental rights of Baha'is," Stork said. "The immediate and unconditional release of the seven Baha'i leaders would be a good start."

UNPO: Southern Azerbaijan: 50 Azerbaijani Arrested by Security Forces

Supporters of the Tabriz soccer team – often seen a followers of the Southern Azerbaijan National Movement – have been arrested by Iranian state security forces after protesting the decision to boycott the Tractor team.

Below is an article published by SANAM:

According to the report from Mr. Aghri Garadaghli (SANAM representative in Baku, Azerbaijan), more than 50 Southern Azerbaijani Turks have been arrested by the Tabriz Ettelaat (security forces) for protesting boycotts against the Tabriz soccer team, Tractor. Tens of fans and activist have been arrested for no solid reason. These innocent people were peacefully protesting the boycott decision of the Iranian soccer league against Tractor soccer club.

Tractor soccer club is a home team of Tabriz and its fans are known for being supporters of the Southern Azerbaijan National Movement. In matches against other large soccer clubs, Tractor fans are known for giving national slogans such as “long live Azerbaijan, down with its enemies”, “down with Persian fascism” and many more. Tractor fans were enraged when the Iranian soccer league announced that Tractor soccer team was going to have matches without its fans for the next few matches. As a result many supporters poured in to streets of Tabriz to peacefully protest this meaningless decision that is intended to target the national awakening movement of the Southern Azerbaijani Turks.

SANAM condemns the inhumane decisions and policies of the Iranian regime. Iranian regime is a member of the United Nations (UN) but it is clear that it does not obey to international laws nor regards the International declaration of human rights. SANAM is trying to help the voices of innocent people reach to international media and organizations. Any action against humanity is considered violation of human rights. The mullah regime has committed uncounted numbers of violations against the national and human rights of 35 million Southern Azerbaijani Turks and millions of other non-Persian ethnics who live in the country called Iran.

Below are the names of 8 fans/activist who were arrested as of August 1 2010:

Ali Zamani, Gulamriza Razmi, Nima Khanlou, Murtaza Salmani, Ali Aghazade, Akbar Yavari, Mahammedtaghy Asadiyan ve Ali Hagigetchudur.

Monday 2 August 2010

HRW: Iran: Release and Provide Urgent Medical Care to Jailed Activist

Mohammad Sadigh Kaboudvand May Have Suffered Stroke; Family Claim He is Not Receiving Adequate Health Care

July 28, 2010

(New York) - The Iranian Judiciary should provide urgent medical care to Mohammad Sadigh Kaboudvand and free him from his unfair detention, Human Rights Watch said today. Kaboudvand, a leading advocate of Kurdish rights in Iran, is serving an 11-year sentence on politically motivated charges. He suffered what may have been a stroke on July 15, 2010, and his family says he is not getting the medical attention he needs.

On July 20, Kaboudvand wrote an open letter to the public prosecutor's office saying that he experienced "brain and neurological problems... that caused loss of consciousness during the afternoon of July 15." Prison authorities transferred him to the Evin prison clinic, which diagnosed a sharp rise in his blood pressure, but failed to treat him. In his letter, Kaboudvand wrote that since he lost consciousness he has been experiencing "intense light-headedness and neurological issues associated with sensory, motion and sight difficulties." His lawyer, Nasrin Sotoudeh, told Human Rights Watch that on July 15 she appealed to judiciary officials to allow Kaboudvand access to the medical treatment he needs, but that her request has gone unanswered.

"Kaboudvand needs an immediate and thorough assessment of his worsening condition. Denying a prisoner necessary medical care is both cruel and unlawful," said Joe Stork, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. "Iranian authorities are responsible for his well-being and should immediately ensure he can get the medical attention he needs."

Kaboudvand has suffered two heart attacks since his arrest and detention in July 2007. Information about Kaboudvand's condition comes on the heels of reports by the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran and Amnesty International indicating that prison authorities are systematically denying needed medical care to political prisoners.

International and Iranian law requires prison authorities to provide detainees with adequate medical care. Iran's State Prison Organization regulations state that if necessary detainees must be transferred to a hospital outside the prison facility. The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners require that authorities transfer prisoners needing specialist treatment to specialized institutions, including civilian hospitals.

On July 23, Kaboudvand's sister told Human Rights Watch that authorities finally allowed her brother to see a neurologist in prison earlier that day. She said that instead of examining her brother thoroughly or administering tests, the doctor prescribed a series of pills and instructed Kaboudvand to take them daily without telling him what they were. Kaboudvand's sister also told Human Rights Watch that authorities have denied him visitation rights and allow him to talk on the phone for only two minutes a day.

Kaboudvand is a prominent human rights defender, journalist, and founder in 2005 of the Human Rights Organization of Kurdistan (HROK). The group grew to include 200 local reporters throughout the Kurdish regions of Iran and provided timely reports in the now banned newspaper Payam-e Mardom (Message of the People), of which Kaboudvand was the managing director and editor.

Intelligence agents arrested Kaboudvand on July 1, 2007, and took him to Ward 209 of Evin Prison, which is under Intelligence Ministry control and is used to detain political prisoners. They held him without charge in solitary confinement for nearly six months. In May 2008, Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court sentenced Kaboudvand to 10 years in prison for "acting against national security" by establishing the Human Rights Organization of Kurdistan, and another year for "widespread propaganda against the system by disseminating news, opposing Islamic penal laws by publicizing punishments such as stoning and executions, and advocating on behalf of political prisoners." In October 2008, Branch 54 of the Tehran Appeals Court upheld his sentence.

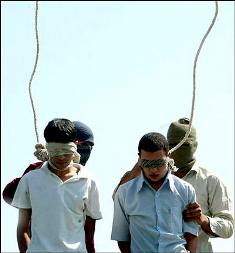

Kaboudvand is among dozens of Kurdish dissidents imprisoned by Iranian authorities, some of them on death row. The authorities routinely accuse Kurdish dissidents, including civil society activists, of belonging to armed separatist groups. Iran's revolutionary courts have convicted many Kurdish dissidents of moharebeh, or "enmity with God." Under articles 186 and 190-91 of Iran's penal code, anyone charged with taking up arms against the state, or belonging to organizations that take up arms against the government, may be considered guilty of moharebeh and sentenced to death. Earlier this year, authorities executed Farzad Kamangar and three other Kurdish dissidents on these charges.

Currently, 16 Kurdish dissidents face execution, they are: Zeynab Jalalian, Rostam Arkia, Hossein Khezri, Anvar Rostami, Mohammad Amin Abdolahi, Ghader Mohammadzadeh, Habibollah Latifi, Sherko Moarefi, Mostafa Salimi, Hassan Tali, Iraj Mohammadi, Rashid Akhkandi, Mohammad Amin Agoushi, Ahmad Pouladkhani, Sayed Sami Hosseini, and Sayed Jamal Mohammadi.

Human Rights Watch has previously called on the Iranian government to end Kaboudvand's unjust sentence and allow him access to urgent medical care. In 2009, Human Rights Watch awarded Kabouvand a Hellman/Hammett grant given to writers who face persecution for criticizing officials or policies, or writing about controversial topics.

"The Iranian authorities have unfairly jailed Kaboudvand because of his work as a human rights defender and journalist promoting ethnic minority rights," Stork said. "Now they appear to be denying him appropriate medical assessment as a way of further punishing him for his peaceful political activities."

July 28, 2010

(New York) - The Iranian Judiciary should provide urgent medical care to Mohammad Sadigh Kaboudvand and free him from his unfair detention, Human Rights Watch said today. Kaboudvand, a leading advocate of Kurdish rights in Iran, is serving an 11-year sentence on politically motivated charges. He suffered what may have been a stroke on July 15, 2010, and his family says he is not getting the medical attention he needs.

On July 20, Kaboudvand wrote an open letter to the public prosecutor's office saying that he experienced "brain and neurological problems... that caused loss of consciousness during the afternoon of July 15." Prison authorities transferred him to the Evin prison clinic, which diagnosed a sharp rise in his blood pressure, but failed to treat him. In his letter, Kaboudvand wrote that since he lost consciousness he has been experiencing "intense light-headedness and neurological issues associated with sensory, motion and sight difficulties." His lawyer, Nasrin Sotoudeh, told Human Rights Watch that on July 15 she appealed to judiciary officials to allow Kaboudvand access to the medical treatment he needs, but that her request has gone unanswered.

"Kaboudvand needs an immediate and thorough assessment of his worsening condition. Denying a prisoner necessary medical care is both cruel and unlawful," said Joe Stork, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. "Iranian authorities are responsible for his well-being and should immediately ensure he can get the medical attention he needs."

Kaboudvand has suffered two heart attacks since his arrest and detention in July 2007. Information about Kaboudvand's condition comes on the heels of reports by the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran and Amnesty International indicating that prison authorities are systematically denying needed medical care to political prisoners.

International and Iranian law requires prison authorities to provide detainees with adequate medical care. Iran's State Prison Organization regulations state that if necessary detainees must be transferred to a hospital outside the prison facility. The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners require that authorities transfer prisoners needing specialist treatment to specialized institutions, including civilian hospitals.

On July 23, Kaboudvand's sister told Human Rights Watch that authorities finally allowed her brother to see a neurologist in prison earlier that day. She said that instead of examining her brother thoroughly or administering tests, the doctor prescribed a series of pills and instructed Kaboudvand to take them daily without telling him what they were. Kaboudvand's sister also told Human Rights Watch that authorities have denied him visitation rights and allow him to talk on the phone for only two minutes a day.

Kaboudvand is a prominent human rights defender, journalist, and founder in 2005 of the Human Rights Organization of Kurdistan (HROK). The group grew to include 200 local reporters throughout the Kurdish regions of Iran and provided timely reports in the now banned newspaper Payam-e Mardom (Message of the People), of which Kaboudvand was the managing director and editor.

Intelligence agents arrested Kaboudvand on July 1, 2007, and took him to Ward 209 of Evin Prison, which is under Intelligence Ministry control and is used to detain political prisoners. They held him without charge in solitary confinement for nearly six months. In May 2008, Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court sentenced Kaboudvand to 10 years in prison for "acting against national security" by establishing the Human Rights Organization of Kurdistan, and another year for "widespread propaganda against the system by disseminating news, opposing Islamic penal laws by publicizing punishments such as stoning and executions, and advocating on behalf of political prisoners." In October 2008, Branch 54 of the Tehran Appeals Court upheld his sentence.

Kaboudvand is among dozens of Kurdish dissidents imprisoned by Iranian authorities, some of them on death row. The authorities routinely accuse Kurdish dissidents, including civil society activists, of belonging to armed separatist groups. Iran's revolutionary courts have convicted many Kurdish dissidents of moharebeh, or "enmity with God." Under articles 186 and 190-91 of Iran's penal code, anyone charged with taking up arms against the state, or belonging to organizations that take up arms against the government, may be considered guilty of moharebeh and sentenced to death. Earlier this year, authorities executed Farzad Kamangar and three other Kurdish dissidents on these charges.

Currently, 16 Kurdish dissidents face execution, they are: Zeynab Jalalian, Rostam Arkia, Hossein Khezri, Anvar Rostami, Mohammad Amin Abdolahi, Ghader Mohammadzadeh, Habibollah Latifi, Sherko Moarefi, Mostafa Salimi, Hassan Tali, Iraj Mohammadi, Rashid Akhkandi, Mohammad Amin Agoushi, Ahmad Pouladkhani, Sayed Sami Hosseini, and Sayed Jamal Mohammadi.

Human Rights Watch has previously called on the Iranian government to end Kaboudvand's unjust sentence and allow him access to urgent medical care. In 2009, Human Rights Watch awarded Kabouvand a Hellman/Hammett grant given to writers who face persecution for criticizing officials or policies, or writing about controversial topics.

"The Iranian authorities have unfairly jailed Kaboudvand because of his work as a human rights defender and journalist promoting ethnic minority rights," Stork said. "Now they appear to be denying him appropriate medical assessment as a way of further punishing him for his peaceful political activities."

ai: Iran must release or try US hikers held without charge for a year

Amnesty International has called on the Iranian authorities to release three US nationals who have been detained without charge or trial for a year.

Shane Michael Bauer, Joshua Felix Fattal and Sarah Emily Shourd were arrested by Iranian forces while they were hiking in the Iraq-Iran border area on 31 July 2009.

"One year on from their arrest it appears clear that the Iranian authorities do not have substantial grounds to prosecute these three individuals, and we fear that they may be held on account of their nationality," said Malcolm Smart, director of Amnesty International's Middle East and North Africa Programme.

"If so, they should be released immediately and allowed to leave Iran."

"If they are not to be freed, they must be charged with recognizably criminal offences and be tried according to international standards for a fair trial."

Iranian officials have alleged that the three planned to carry out "acts of espionage" in Iran. Their families and the US government deny this and the three have not been formally charged.

Iranian claims that the three were arrested after straying into Iran have been challenged by The Nation, an American weekly news publication, which said it had eyewitness testimony that they were seized in Iraq by Iranian Revolutionary Guards and taken forcibly into Iran.

Statements by senior Iranian leaders - including President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in February 2010 - have suggested that the three may be being detained in order to put pressure on the US government and to extract diplomatic concessions.

"If this were the case, then the continuing detention of these three individuals would amount to hostage-taking and be a very serious abuse of human rights," said Malcolm Smart.

One year after their arrest, the Iranian authorities' failure to charge them with illegal entry into Iran or more serious charges, such as espionage, has fuelled speculation that the Iranian authorities are holding them as a bargaining chip.

"We believe that their questioning ended several months ago, so if serious charges were being considered these should have been brought by now."

The three are held at Tehran’s Evin Prison. They were allowed to telephone their families only several months after their arrest but in May 2010 they were taken to a Tehran hotel and allowed to meet their mothers who had travelled to Iran from the USA.

An Iranian lawyer appointed by their families to represent the three has not been given access to them and Swiss embassy officials, who represent US consular interests in Iran, have not been allowed to visit them since last April.

The families of two of the detainees, Sarah Shourd and Shane Bauer, say they have health problems which require regular monitoring.

"The detainees must be given immediate access to their lawyer, to renewed consular access and contact with their families, and to any medical attention or treatment that they need," said Malcolm Smart.

"The Iranian authorities must release these three US nationals without delay and allow them to leave Iran unless they are to face recognizable criminal charges and be tried promptly according to recognized international standards for fair trial."

jewishjournal.com: Remembering Ebi: Why we fled Iran

“I will never forget when I first saw his body — they shot him with one bullet at point-blank range in his heart,” my father, George Melamed, shared with me a few weeks ago, reflecting on his friend — and brother-in-law’s brother — Ebrahim (Ebi) Berookhim, who was executed in an Iranian prison on July 31, 1980, at the age of 30. For the past 30 years, my father has rarely spoken of this young Jewish man’s killing and the circumstances that propelled our family’s abrupt flight from Iran. During these past three decades, he’s tried to forget how Ebi was unjustly accused of being an Israeli and American spy, then ruthlessly murdered by Iran’s radical Islamic regime.

Yet as Ebi’s 30th yahrzeit approached this month, my parents, our relatives and some local Iranian Jews who knew this successful young Jewish businessman finally opened up to me about this tragedy that completely transformed all of our lives.

With news of the Iranian government’s pursuit of nuclear weapons continually filling today’s airwaves, the story of Ebi’s killing serves as a stark reminder to us all of the continuing brutality and illogical nature of the ayatollahs’ regime in Iran. The Iranian government’s inhumane practice of random arrests and imprisonment of innocent individuals continues to this day: On July 31, 2009, the same date that Ebi died but 29 years later, three American hikers were randomly taken hostage in Iran for mistakenly crossing a border; they remain unfairly imprisoned. Last year, Roxana Saberi, an Iranian American journalist based in Tehran, was arrested on false charges of espionage — she was one of the lucky ones; after immense pressure from abroad, the Iranian authorities released her.

Ebi, my relative, wasn’t so lucky. And the pain of losing him continues to haunt our family three decades later. The person closest to Ebi during the final months of his life was his elder sister, Shaheen Makhani, who today is a businesswoman and grandmother living in Santa Monica. I met with her and her family earlier this month, and they wept silently as they told me their story, speaking publicly for the first time about Ebi and his tragic demise.

“He was four years younger than me. We were very close, and I loved him,” Shaheen told me. “He had just returned from America after getting his degree, and he had also completed his mandatory military service in the Iranian army. He had his whole future ahead of him.”

Shaheen said Ebi’s problems started with the beginning of Iran’s Islamic revolution, in early 1979, when the Berookhim family’s five-star Royal Gardens hotel in Tehran was confiscated by the newly formed Islamic regime of the Ayatollah Khomeini. Nearly all of his family had already fled Iran for the United States in the prior months, but Ebi remained behind. One day, armed thugs of the regime overran the hotel and quickly blindfolded him. They took him to the Khasr prison in Tehran on trumped-up charges of being an American and Israeli spy.

“We knew they had arrested and imprisoned Ebi in order to get at our family’s other assets, and therefore it was not easy to get him out of prison,” Shaheen said. “It was a nightmare because we didn’t know what they were going to do with Ebi.”

I recently discovered that while Ebi was in Khasr prison, he befriended other Jews who also were unjustly being held captive, including Behrooz Meimand, now a 64-year-old insurance salesman living in Los Angeles. Meimand told me recently that “until the last day we were in the Khasr prison, Ebi and I were together, and he often rested his head in my lap and wept — I felt as if he was like my younger brother, and I tried to comfort him during the difficult days.”

Ebi’s sister Shaheen said that two months after her brother was captured, she was finally able to get him released from prison, but only after paying what she said were ridiculously large bribes and other payments to the prison officials.

Each and every one of Ebi’s family members and friends whom I spoke with said they urged Ebi to escape from Iran after his release from prison, but he responded negatively to them all.

My father recalled one conversation he had with Ebi after a Shabbat dinner following Ebi’s release: “I told him to get the hell out of Iran because these people in the government had a case against him and wanted his family’s properties — but he responded, ‘No, no, no ... my family and I are innocent. We didn’t do anything wrong or illegal. Why should I leave?’ ”

This mistake of remaining in Iran proved fatal for Ebi. But he didn’t see what was coming. Shaheen said that, in the months after Ebi’s first arrest, he and his 82-year-old father, Eshagh Berookhim, voluntarily visited the infamous Evin prison, located just north of Tehran, because they believed promises the Iranian officials had made to them — that their hotel would be returned when they agreed to present their case at the prison. Then, one morning, in April 1980, during one of these voluntary visits, the Evin prison authorities arrested Ebi again and sent him to prison. This time, his elderly father was arrested with him.

Over the next nearly four months, Shaheen worked tirelessly to free them. Then, early one morning, she turned on the radio and was devastated to learn that her beloved brother had been executed at the prison earlier that same day.

Around the same time, my father heard the news from a co-worker, and he, too, was shocked. Without hesitation, my father and three other Jews risked their lives by going to the prison morgue to retrieve Ebi’s body because most of his family was no longer in Iran to give him a kosher burial. Ebi’s father was still being held.

“It was dangerous at the time to get his body because the authorities would ask what relationship you have with the infidel who was executed or demand to see your identification. And they could create all sorts of future problems for you,” my father told me. “But I nevertheless went with a few others, because Ebi was a close friend of mine and a family member whom we could not allow to be buried in a mass grave with the other executed political prisoners.”

The regime’s prison officials refused to release Ebi’s body until a substantial payment was made to “cover the costs for the bullet used in the execution,” he said.

My father and the other Jewish men paid and were eventually given Ebi’s bloody body. My father recalled: “Ebi’s body was still warm while he lay in the mortuary at the Jewish cemetery; it had been desecrated with markers, and the soles of his feet showed signs that he had been tortured with steel wiring.” He also said, “You could tell he was shot at point-blank range, because the opening was a half an inch in diameter on the front of his body near his heart, and the hole on his back side was two or three inches wide.”

Shaheen, her husband, Masood, and other friends and family were at Ebi’s burial in Tehran’s Jewish cemetery. Several weeks later, Shaheen said she was able to bribe the prison officials by paying them a substantial amount of money to release her elderly father, who had been moved to the prison hospital due to his poor health. When he was released, Eshagh repeatedly asked for Ebi but was not told of his beloved son’s execution. Instead, Eshagh was hidden inside another family member’s home, then smugglers were paid to carry him on a camel across the border out of Iran and into Turkey. Shaheen said that, at the same time, she and her husband were fortunate enough to flee Iran on a flight to Germany. Only after the three were reunited in Germany were they able to mourn Ebi in peace. It was there that she finally broke the news of Ebi’s execution to her father.

My mother, Roset Melamed, recalled for me the immediate aftereffects that Ebi’s execution had on my own father, who had been Ebi’s close childhood friend.

“When your father returned, after he had seen Ebi’s body and had been to the funeral, he was no longer the same happy and carefree man as before,” she told me. “It was as if something inside of him died. He did not want to listen to music anymore; he did not want to play with you, his young son, who was so sweet and starting to talk. He just stared at you for long periods of time, and it seemed as if life did not matter anymore to him.”

Another of Ebi’s older sisters, Negar Berookhim, told me that the entire Iranian Jewish community living in Los Angeles at the time was shocked and infuriated when they learned of Ebi’s execution. She said that nearly 1,000 members of the community flooded Sinai Temple in West Los Angeles for a memorial seven days after his killing.

Even though the Iranian government never officially announced its reasons for executing Ebi, his friends, family and other Iranian Jews living in Southern California have their own theories. Some believe he was executed to strike fear into the hearts of Jews in Iran, to force them to abandon their substantial assets so the government could confiscate them. Others believe the execution may have been an act of revenge by the Iranian clerics and Palestinian terrorists in Iran following Israel’s declaration of Jerusalem as its undivided and eternal capital not long before this time. A few individuals close to the Berookhim family also believe that some of their hotel’s former disgruntled employees who had become officials in the new regime may have conspired to have Ebi killed out of jealousy or in order to confiscate his family’s wealth.

My parents told me that Ebi’s execution was the final breaking point in their decision to flee Iran and leave behind all our assets; we left in September 1980. As it turned out, we were among the last to flee Iran via plane; Tehran’s international airport was shut down just three days after our flight because of the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War. We traveled first to Germany, where my father had relatives living in Hamburg, but we had not had time to obtain entry visas amid the chaos of our departure from Iran. Once again, we were immensely fortunate — the immigration agent granted my family visas at our arrival after my father spoke fluently to him in German and explained our predicament.

From Germany, we had a brief stay in Israel, and then, two months after leaving our Iranian home, we finally immigrated to Los Angeles, where my parents restarted their lives from zero.

Even so, my parents recently admitted to me that they probably would have remained in Iran to this day, to care for my elderly grandparents, had Ebi not been executed. And the ripples from his death went even further. Ebi’s execution caused another massive wave of Jews in Tehran and elsewhere in Iran to sell what assets they could at bargain prices and flee the country.

Ebi was officially only the third Jew to be executed by the Islamic government in Iran. Two other more prominent Jews were executed before him on similar false charges of espionage for Israel and the United States. The first was Habib Elghanian, the leader of Iran’s Jewish community, who was executed in May 1979. The second was the well-known Jewish businessman Albert Danielpour, who was executed in June 1980 in the city of Hamadan.

According to a 2004 report prepared by Frank Nikbakht, an Iranian Jewish activist who heads the Los Angeles-based Committee for Minority Rights in Iran, the Jewish community in Iran continues to live in constant fear for its security amid threats from Islamic terrorist factions. Since 1979, at least 14 Jews have been murdered or assassinated by the regime’s agents, at least two Jews have died while in custody, and 11 Jews have been officially executed by the regime. In 1999, Feizollah Mekhoubad, a 78-year-old cantor of the popular Yousefabad synagogue in Tehran, was the last Jew officially to be executed by the regime, according to the report.

In 2000, with the assistance of various American Jewish groups, the Iranian Jewish community in the United States, but particularly in Los Angeles, was able to publicize the case of 13 Iranian Jews from the city of Shiraz who had been imprisoned in 1999 on fabricated charges of spying for Israel. Ultimately, the international exposure put pressure on the Iranian regime, and the “Shiraz 13” eventually were released.

Despite the painful memories surrounding the execution of Ebi, our family members, like my relative Abraham Berookhim — Ebi’s nephew — said they do not harbor ill will toward Iranian Muslims in general.

“I don’t want people to think that all Muslims are bad, because it’s not true — some of my friends and even my business partner are Muslims and they’re great people,” Abraham told me. “We oppose the regime of Iran and their radical leadership.”

But the lasting effects of Ebi’s execution are still felt by my parents and the rest of our family. The emotional scars from 30 years ago have not fully healed for any of them. For the first time since Ebi’s execution, my father openly admitted that many nights he is still haunted by nightmares of the tragedy. “Even though I have nightmares of what happened to Ebi, I wanted to talk about how Ebi was killed,” my father said, “because I want others to know what an injustice happened to an innocent man.” And despite experiencing tremendous hardships and persecution at the hands of the radical Islamic regime in Iran, the Iranian Jewish community in Southern California continues to be active in seeking to help its 20,000 Jewish brethren who remain there.

And the American Iranian Jews won’t be silenced: In September 2006, a lawsuit was filed against former Iranian President Mohammad Khatami in a U.S. federal court by the families of 12 Iranian Jews arrested by the Iranian secret police while attempting to flee from southwestern Iran into Pakistan between 1994 and 1997; the 12 were never heard from again. The suit alleges Khatami authorized the arrest and indefinite imprisonment of those 12 Iranian Jews. While the regime never defended its case in court, the suit kept alive the story of the 12 missing Jews in the public eye and kept the spotlight on the Iranian regime’s human rights abuses.

After hearing their family’s stories of struggling and escaping from Iran, likewise many young professionals in the Iranian Jewish community, including the organization 30 Years After, continue to work hard to have their voices heard. It is stories like my cousin Ebi’s that refuse to die and that have brought a new generation of Iranian Jews to embrace political involvement in their homeland, the United States, when it comes to issues of Iran.

SDGLN: More arrests of gay men reported in Iran

On Sunday, July 11, 2010, a private party in a suburb called Podonak was raided. The police lead the raid, accompanied by the volunteer moral militia (Basij) and revolutionary guard (Sepah). Reports vary, but we understand that between 17 and 19 people have been arrested and taken to the local intelligent service’s detention centre on Modares Boulevard

Their police files are labeled “Gang of Faggots in Shiraz” and their homes have been raided and personal belongings confiscated by the police. They are to be tried today, in both the Revolutionary and the General Courts, Shiraz.

Since the raid, we have been able to confirm the names of nine people who have been arrested and labeled as a “Gang of Faggots in Shiraz” and we do not have information about the rest of them.

We understand that the police are going to entrap more queers in Shiraz, Esfahan and Mashhad, and fear that more arrests might take place in the coming days. We advise Iranian queers to be extremely careful with their safety, and to be aware that phones in Iran can and are being tapped. Most queers in Shiraz have deleted their Yahoo IDs, profiles, facebook accounts and other cyber communication. We have heard rumors that a party has been raided in Esfahan, but have not yet confirmed this.

The Iranian authorities have a long record of arresting and torturing LGBTQ Iranians.

For example, in September 2003, in Shiraz, a group of men were arrested at a private party in one of the men’s houses. They were held in detention for several days, where, according to one of the men, police tortured them to obtain a confession. They were tried for “participation in a corrupt gathering” and fined.

In June 2004, also in Shiraz, police arranged meetings with men through internet chat rooms. Once arrested, the men were repeatedly beaten and tortured, and sentenced to 175 lashes, 100 administered immediately. Since their arrest, police have subjected the men to regular surveillance and periodic arrests.

On May 10, 2007, eighty-seven men were arrested and beaten by the police at a birthday party in Esfahan. The police turned off the lights, shot blanks from their guns, forced everyone to lie on the ground, then walked over to them and began beating them. The police then covered the guests’ heads with bags or blouses, forced them out into the street and pushed them with batons into a military transport. The people who witnessed the event on the street reported that the clothes of the arrested men were torn and that their faces were bleeding.

On July 8, 2010, Mohammad Mostafai, an Iranian lawyer announced that three of his four clients were cleared of sodomy charges, but one, an eighteen year old youth named Ebrahim Hamidi, was sentenced to be executed.

Also on June 18, 2010 we received reports from Iran regarding three more possible death sentences for homosexuality, one man receiving 74 lashes for his homosexual act and the murder of a 23 year old bisexual man by the Iranian security forces.

These many incidents are just some of the many examples that reveal the extent to which the walls of private homes in Iran are transparent and the halls of justice opaque. It also reveals that the authorities and Islamic government's respect for privacy and personal dignity is nonexistent in Iran.

We at IRQR call on the Iranian government to end these arrests of LGBQ Iranians and to respect the basic human rights of its citizens.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)