Iran

executions by stoning

© AP

“We have to work to eradicate stoning

wherever it happens in the world: it is a

brutal and inhuman act… through which

the authorities are attempting to control

society [and stop] people enjoying their

right to a private life.”

Shadi Sadr, Iranian lawyer, anti-stoning campaigner

and women’s rights activist

Ja’far Kiani was buried up to his waist and

stoned to death on 5 July 2007 in Iran’s

north-western province of Qazin. He had

been convicted a decade earlier of “adultery

while married” with Mokarrameh Ebrahimi,

with whom he had two children and who

was also sentenced to death by stoning. Her

life was later spared.

Stoning is mandatory under the Iranian

Penal Code for “adultery while married” for

both men and women – conduct that the

vast majority of states do not criminalize, let

alone punish with death.

Stoning is a particularly repugnant and

cruel form of execution. Iranian law

specifies that the stones must be large

enough to cause injury and eventually

death, but not so large as to kill the victim

immediately. This form of execution is

therefore deliberately designed to prolong

the suffering of victims.

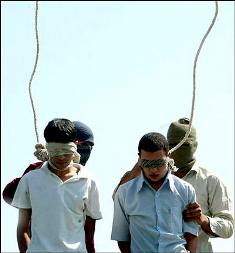

The most common method of execution in

Iran is hanging, and hundreds of men and

women are put to death this way every year.

Since the Islamic Revolution of 1979,

Amnesty International has documented at

least 77 stonings, but believes the true

figure may well be higher, particularly as

it was not able to record figures for all the

years between 1979 and 1984.

Those sentenced are frequently poor or

otherwise marginalized members of society.

Most of those sentenced to death by

stoning are women for the simple reason

that they are disadvantaged in the criminal

justice system, and face wide-ranging

discrimination in law, particularly in regard

to marriage and divorce. However, in recent

years more men are known to have been

stoned to death than women.

In 2002, the then Head of the Judiciary

declared a moratorium on stoning. However,

Iranian law gives judges wide discretionary

powers when deciding on sentencing, and

since 2002 at least five men and one woman

have been stoned to death. Additionally, at

least two men and one woman sentenced

to stoning have been hanged instead. In

January 2009, the Spokesperson for the

Judiciary stated that the directive to judges

on the moratorium had no legal weight and

that judges could ignore it.

In June 2009, the Legal and Judicial

Affairs Committee of Iran’s parliament

recommended the removal of a clause

permitting stoning from a new draft revision

of the Penal Code. This remains under

discussion in parliament.

A draft submitted for comment to the

Council of Guardians, which checks

legislation for conformity to the Constitution

and Islamic law, is reported to omit any

reference to the penalty of stoning.

However, either the parliament or the

Council of Guardians could reinstate the

clause on stoning. In addition, even if

the penalty is removed from law, stoning

sentences could still be imposed by judges

under legal provisions that require them to

judge cases by their knowledge of Islamic

law where no codified law exists.

Amnesty International opposes the death

penalty in all cases as a violation of the right

iran

ExEcutIonS by StonIng

2

amnesty international December 2010 Index: mdE 13/095/2010

Death by stoning is the manDatory sentence for “aDultery

while marrieD” in iran. EvEn though a moratorIum on Such

ExEcutIonS waS announcEd In 2002, StonIngS contInuE.

amnESty IntErnatIonal IS workIng alongSIdE thE many IranIanS

who arE campaIgnIng to End Iran’S rESort to thIS partIcularly

abhorrEnt mEthod of ExEcutIon.

to life and the ultimate form of cruel,

inhuman and degrading punishment. A

cornerstone of its campaigning is that laws

and judicial proceedings should conform to

internationally recognized human rights

standards and that governments must abide

by their international human rights

obligations.

Iran is a state party to the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

(ICCPR). The government is therefore

legally bound to observe the provisions of

this treaty and to ensure that they are fully

reflected in the country’s laws and

practices. Death by stoning violates Articles

6 (right to life) and 7 (prohibition of torture

and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment

or punishment) of the Covenant.

The Special Rapporteur on torture, the

Human Rights Committee, the Committee

against Torture and the Commission on

Human Rights have all said that stoning –

a form of corporal punishment – is contrary

to the prohibition of torture and other cruel,

inhuman or degrading treatment or

punishment and should not be used as a

method of execution.

In addition, international human rights

standards require that death sentences

must only be imposed after trials which

fully meet international fair trial standards.

These include the right to adequate legal

assistance at all stages of the proceedings,

the right not to be forced to testify against

oneself or to confess guilt, and the right to

appeal to a higher judicial body, as laid out

in Articles 6(2) and 14 of the ICCPR.

Amnesty International has long expressed

concern over the fairness of trials in Iran,

including the routine use of torture or other

ill-treatment to extract “confessions” and

denial of access to lawyers during pre-trial

interrogation, as well as provisions that allow

the judge in some instances to use his

subjective “knowledge” of the case as the

sole basis of conviction.

Index: mdE 13/095/2010 amnesty international December 2010

iran

ExEcutIonS by StonIng

3

‘The size of the stone used in

stoning shall not be so big as

to kill the person by one or two

throws, nor so small that it

cannot be called a stone.’

article 104 of Iran’s Islamic penal code

dIScrImInatIon agaInSt womEn

‘Stoning is a method of capital punishment primarily used for crimes of

adultery and other related offences, of which women are disproportionately

found guilty, which is inconsistent with the prohibition of discrimination on

the basis of sex enshrined in all major human rights instruments.’

manfred nowak, un Special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, 15

January 2008

the punishment of death by stoning in Iran has a disproportionate impact on women. one

reason is that women are not treated equally before the law and courts, in clear violation of

articles 2, 3, 14 and 26 of the Iccpr. In court, in relation to some offences including adultery, a

man’s testimony is worth that of two women, and testimony by women alone is not accepted.

In a country where the literacy rate of women is lower than that of men, women are more

susceptible to unfair trials as they are more likely to sign false “confessions” that they have

not understood. they are generally poorer than men as their job opportunities are restricted,

which means they are less able to obtain good legal advice. women from ethnic minorities are

less likely than men in their communities to speak persian, the language of courts, so they

often do not understand what is happening to them in the legal process or even that they face

death by stoning.

discrimination against women in other aspects of their lives also leaves them more susceptible

to conviction for adultery. men are allowed four permanent wives and an unlimited number of

temporary wives, but women are only permitted one husband at a time. they also have a limited

right to divorce, unlike men who have the right to divorce at will. many women have no choice

over the man they marry and many are married at a young age.

women face strict and discriminatory controls on their behaviour, such as an officially enforced dress

code that requires them to be veiled, and limitations on their freedom of movement, which are

imposed and/or policed by the state. despite such controls and some gender segregation, when

women come into conflict with the law they are usually arrested, interrogated and judged by men who

are unlikely to be sensitive to gendered aspects of the case or who may be prejudiced against women.

finally, even the stoning procedure specified in law discriminates against women – men must

be buried in a pit up to near the waist; women up to near the chest. this has added

significance as the law also states that if a condemned person escapes from the pit, they

cannot be stoned again if their conviction was based on a confession.

conDemneD to stoning

At least 10 women and four men are

believed to be at risk of death by stoning,

although several cases are still under review

and alternative sentences may be imposed.

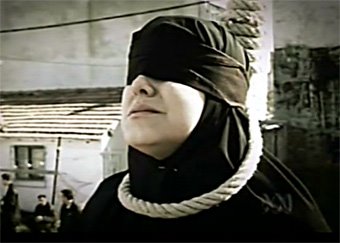

At least one other woman, Maryam

Ghorbanzadeh, originally sentenced to

stoning (see picture below), is facing

execution by hanging for “adultery while

married”.

The case of Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani

has generated widespread international

attention. She was convicted in 2006 after

an unfair trial for “adultery while married”.

She was also separately convicted of

murder, later reduced to complicity in

murder for which she was sentenced to five

years’ imprisonment.

A 43-year-old mother of two from Iran’s

Azerbaijani minority, she speaks Azerbaijani

Turkic and has limited knowledge of

Persian, the language used by the courts.

She did not know that the Arabic loan word

rajm used when she was sentenced meant

stoning, and fainted with shock when fellow

inmates explained.

She was found guilty by three of the five

judges who heard her case. Although she

told the court that her “confession” had

been forced out of her and was not true, the

three judges convicted her on the basis of

“the knowledge of the judge”, a provision

in Iranian law that allows judges to decide

on subjective grounds whether or not a

defendant is guilty even if there is no clear

or conclusive evidence. In May 2007 the

Supreme Court confirmed the stoning

sentence. Later still, the Amnesty and

Clemency Commission twice rejected her

requests for clemency.

Since her case became the focus of

widespread international campaigning, the

Iranian authorities have made several

unclear and sometimes contradictory

statements relating to her legal status and

likely fate. The authorities appear to be

attempting to deflect criticism by portraying

her as a dangerous criminal who deserves

to be executed. She remains on death row

in Tabriz’ Central Prison and has been

denied visits by her children and lawyer

since August 2010.

Another woman from Iran’s Azerbaijani

minority, 19-year-old Azar Bagheri, was

sentenced to stoning. Married at 14, she

was no more than 15 when arrested. An

appeal court subsequently changed the

sentence to flogging, but her lawyer remains

concerned that stoning may be re-instated

by the Supreme Court, which is currently

reviewing the case.

Iran Eskandari, a woman from the Bakhtiari

tribe in the south-western province of

Khuzestan, was sentenced to stoning for

adultery and five years in prison for being

an accomplice in the murder of her

husband, verdicts upheld by the Supreme

Court in April 2006. According to reports,

she was talking to the son of a neighbour in

her courtyard when her husband attacked

her with a knife. She was left bleeding and

unconscious on the floor. While she was

unconscious, the young man allegedly killed

her husband. When police interrogated her,

she reportedly admitted to adultery with her

neighbour’s son, a “confession” she later

retracted. In June 2007 the Discernment

Branch of the Supreme Court overturned

the stoning sentence and sent her case

back for retrial before a criminal court in

Khuzestan. That court reimposed the

stoning sentence. Her case has been with

the Amnesty and Clemency Commission

since February 2009. Iran Eskandari

remains in Sepidar Prison in Ahvaz city.

Also in Khuzestan, Khayrieh Valania was

sentenced to death for being an accomplice

to murder and to execution by stoning for

adultery. According to reports, her husband

was violent towards her and she was having

an affair with a relative of her husband, who

then murdered her husband. Khayrieh

Valania confessed to adultery but denied any

involvement in the murder. Reports indicate

that the verdict has been upheld and the

case sent to the Head of the Judiciary for

permission to carry out the execution.

amnesty international December 2010 Index: mdE 13/095/2010

iran

ExEcutIonS by StonIng

4

Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani, who has lived

with the fear that she may be stoned to death

for more than four years.

© Private amnesty International opposes the

criminalization of consensual sexual

relations between adults and considers

those imprisoned for such acts to be

prisoners of conscience who should be

released immediately and unconditionally.

under international human rights law, nonviolent

acts such as sexual relations

between consenting adults should not be

punishable by death.

Ashraf Kalhori (or Kalhor), aged about 40

and a mother of four, was sentenced to

death by stoning for adultery and to 15

years’ imprisonment for taking part in the

murder of her husband in April 2002. Her

previous request to divorce him had been

rejected by a judge. She says that the killing

was accidental, but police accused her of

having an affair with a neighbour and

encouraging the attack. She was reported

to have “confessed” to adultery under

police interrogation, but later retracted her

statement. She was scheduled to be stoned

before the end of July 2006, but her

execution was stayed temporarily. On 23

February 2009, it was reported that the

Amnesty and Clemency Commission had

rejected her plea and that her sentence

could now be implemented at any time,

although on 2 June 2009, the

Spokesperson for the Judiciary said that

the Amnesty and Clemency Commission

had not yet reached a decision in her case.

Kobra Babaei and her husband Rahim

Mohammadi, who have a 12-year-old

daughter, were sentenced to stoning for

“adultery while married” in April 2008 by a

court in Eastern Azerbaijan Province. The

court also convicted Rahim Mohammadi

of “sodomy” for which the penalty is

execution, “the method to be specified by

the judge”. In April 2009, the Supreme

Court confirmed all the sentences.

According to their lawyer, the couple had

turned to prostitution after a prolonged

period of unemployment. In July 2009, the

Spokesperson for the Judiciary denied that

the couple’s sentences were final, but

Rahim Mohammadi was nevertheless

hanged on 5 October 2009. His lawyer, who

had not been informed of the execution

beforehand, as is required by law, said

afterwards that there was no evidence of

“sodomy” and that he believed this charge

was brought to allow the authorities to hang

Rahim Mohammadi, rather than stone him

to death.

Other women reported to have been

sentenced to stoning in Mashhad but about

whom little else is known are “M. Kh”

(convicted in 2008 and whose case is

believed to be connected to Houshang

Khodadadeh who was stoned to death in

Mashhad in December 2008), and a

woman known only by her family name of

“Hashemi-Nasab”. Their fate remains

unclear.

A 21-year-old woman and a man, Abbas

Hassani, 34 and a father of two, were both

sentenced to stoning in Mashhad by Branch

5 of the Khorassan-e Razavi General Court

in late 2009. Their sentences were upheld

on appeal, and confirmed by the Supreme

Court on 14 June 2010. They were accused

of “adultery while married” after the

woman’s husband made a complaint after

he found mobile phone pictures in his wife’s

possession. Abbas Hassani is reported to

be at imminent risk of execution as his

sentence has been sent to the Office for

the Implementation of Sentences.

Index: mdE 13/095/2010 amnesty international December 2010

iran

ExEcutIonS by StonIng

5

© Private

© Private

Sajjad Qaderzadeh (top), the son of Sakineh

Mohammadi Ashtiani, and (below) Javid

Houtan Kiyan, a lawyer in several cases

involving sentences of death by stoning, have

both been harassed by the authorities.

“Since I am a rural, illiterate

woman and I didn’t know

the law, I thought that if I

confessed to a relationship

with the dead man, I could

clear my brothers and husband

of intentional murder.”

Shamameh (malek) ghorbani, who was sentenced to death

by stoning for adultery, in a letter to the court

amnesty international December 2010 Index: mdE 13/095/2010

iran

ExEcutIonS by StonIng

6

© N. Azimi

Above: Maryam Ghorbanzadeh, aged 25,

was tried in East Azerbaijan province in

September 2009 for “adultery while married”.

In August 2010, at the height of the

international protests about the stoning

sentence against Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani,

Branch 12 of the provincial General Court

sentenced her to stoning but in the same

verdict changed the sentence to death by

hanging based on “the general policy of the

Judiciary and directives to change [stoning]

rulings… to execution by other methods”.

Her lawyer, Javid Houtan Kiyan, submitted a

request for a judicial review, but meanwhile it

is feared that Maryam Ghorbanzadeh could be

executed at any moment.

Left: An Amnesty International protest in

Brussels, Belgium, September 2010, on behalf

of Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani, who faces

death by stoning in Iran.

© Private

Another woman and man – Sarieh Ebadi

and Vali or Bu-Ali Janfeshan – had stoning

sentences against them upheld in August

2010, according to reports. It appears that

at no stage of the legal process were they

allowed lawyers of their choice. They are

said to have been held in Oroumieh

Central Prison, West Azerbaijan province,

since 2008.

Among the men sentenced to stoning is

Mohammad Ali Navid Khomami.

According to a 7 April 2009 report in the

Iranian newspaper Ham Mihan, he was

convicted of “adultery while married” in the

city of Rasht, Gilan province in northern

Iran. No further details are available. Fears

for his life increased after the Spokesperson

for the Judiciary confirmed on 5 May 2009

that another man had recently been stoned

to death in Rasht. This was believed to be

30-year-old Vali Azad from Parsabad,

executed in secret in Lakan Prison on

5 March 2009.

According to an August 2009 report in the

Iranian newspaper Sarmayeh, Naghi

Ahmadi was sentenced to stoning in Sari,

Mazandaran, also northern Iran, in June

2008. His lawyer said that he and a woman

were sentenced after they confessed to

“adultery while married” after Naghi

Ahmadi had gone to the woman’s house

one night when her husband was away.

The woman was apparently not sentenced

to stoning. The reason for this may relate to

Article 86 of the Penal Code, which states

that if “adultery” occurs when a spouse is

away due to “travel, imprisonment or other

extraneous circumstances” the person will

not be stoned to death.

Requests by Amnesty International to the

Iranian authorities for further details about

these and other cases have not received

responses.

campaign against stoning

The campaign against stoning has been

spearheaded from inside Iran by extremely

brave activists. The campaign began on

1 October 2006, when a group of Iranian

human rights defenders, lawyers and

journalists, led by lawyer Shadi Sadr and

journalists Mahboubeh Abbasgholidzadeh

and Asieh Amini, along with other activists

outside Iran, such as Soheila Vahdati, all

horrified at the resumption of stoning in

May that year, launched the Stop Stoning

Forever campaign to abolish stoning in law

and practice. Their courageous efforts have

been supported by international human

rights organizations, including Amnesty

International, and many individuals around

the world.

Since then, at least 13 women and two men

have been saved from stoning. The include

Hajieh Esmailvand, Soghra Mola’i, Fatemeh

A., Shamameh (Malek) Ghorbani,

Mokarrameh Ebrahimi, sisters Zohreh and

Azar Kabiri-niat, a woman known only as

“Hajar”, Kobra Najjar, Leyla Ghomi, Zahra

Rezaei, Gilan Mohammadi and Gholamali

Eskandari who were sentenced in the same

case, and a couple, Parisa A. and her

husband Najaf. Others have been granted

stays of execution, and some cases are

being reviewed or retried.

In the case of Shamameh (Malek) Ghorbani,

an Iranian Kurd condemned to stoning for

adultery in June 2006, her sentence was

overturned after retrial and she was instead

Index: mdE 13/095/2010 amnesty international December 2010

iran

ExEcutIonS by StonIng

7

© Jorn van Eck / Amnesty © Iran Emrooz International

Top to bottom: Shadi Sadr, a lawyer and

journalist; Mahboubeh Abbasgholizadeh,

a filmmaker; and Asieh Amini, a journalist.

All three have played a prominent role in the

End Stoning Campaign and as a result of

their human rights activities have been forced

to flee Iran because of threats or persecution

and now live in exile.

© www.kosoof.com

amnesty international is a global movement of 2.8 million supporters,

members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who

campaign to end grave abuses of human rights.

our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the

universal declaration of human rights and other international human

rights standards.

we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest

or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

sentenced to 100 lashes. Her brothers and

husband had allegedly murdered a man they

found in her house, and nearly killed her by

stabbing. The Supreme Court rejected the

stoning sentence in November 2006 and

ordered a retrial, citing incomplete

investigations. Shamameh Ghorbani had

apparently confessed to adultery, believing

that this would protect her brothers and

husband from prosecution for murder.

Success in preventing stonings has come

for a variety of reasons, including local and

international campaigning and the actions

of lawyers. For example, lawyers have told

Amnesty International that using Islamic

arguments to challenge the legitimacy of

convictions resulting from the “knowledge

of the judge” have been effective in some

cases, as well as obtaining fatwas (religious

rulings) from senior Muslim clerics that

stoning sentences should not be passed.

However, the campaign has faced

repression in Iran and its supporters have

been intimidated and harassed. Some,

including Asieh Amini, Mahboubeh

Abbasgholizadeh and Shadi Sadr, have

been forced to leave the country for their

own safety and now live in exile.

Many lawyers who have represented people

in stoning cases have reported being

threatened and harassed to discourage them

from publicizing the cases. Mohammad

Mostafaei, one of the lawyers linked to the

case of Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani, had

to flee Iran for his safety in July 2010 after

his wife and another relative were detained to

put pressure on him to present himself to the

authorities for questioning. Another lawyer in

the case, Javid Houtan Kiyan, was stopped

by security officials at Tabriz airport in late

August and forcibly taken to his office, where

they removed files. Ten days earlier, security

forces had raided his house in Tabriz and

taken away property, including his laptop

that held information about several stoning

cases. In October 2010, he was arrested

along with Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani’s

son, Sajjad Qaderzadeh (pictured), as they

were giving an interview to two German

journalists. The journalists, who had not

entered the country on journalists’ visas,

were also arrested. Amnesty International

fears that these arrests may be intended to

limit the flow of information to the outside

world about Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani’s

case. In particular, the arrest of her lawyer

leaves her defenceless and at the mercy of

an arbitrary justice system.

Amnesty International is calling on the

Iranian authorities to:

n Reaffirm and fully respect the

moratorium on executions by stoning,

including by ensuring that all individuals

sentenced to stoning will not face execution

for “adultery while married” by other means.

n Enact legislation that bans stoning as a

legal punishment and ensure the draft Penal

Code does not permit the use of any form of

the death penalty or flogging for those

convicted of “adultery” or other crimes.

n Release anyone held solely on the

grounds of consensual sexual relations;

Amnesty International considers such people

to be prisoners of conscience.

n Decriminalize consensual sexual

relations between adults.

n Allow lawyers defending stoning cases to

carry out their work without fear of

persecution.

n Review all legislation in Iran under

which a convicted person may be killed by

the state, with the immediate aim of

progressively restricting the scope of the

death penalty, and with a view to the

eventual abolition of the death penalty.

iran

ExEcutIonS by StonIng

8

“The vast majority of the Iranian people are vehemently opposed

to stoning. There is no history of stoning ever taking place in

Iran before the 1979 Islamic Revolution and most Iranians find

the practice revolting. While many Iranians believe that adultery

is morally wrong… they do not believe that it should be

considered a ‘crime against the state’… In Iran, adultery carries

a harsher punishment than murder, and this offends the

sensibilities of [many] Iranians.”

the global campaign to Stop killing and Stoning women, July 2010

Index: mdE 13/095/2010

English

december 2010

amnesty International

International Secretariat

peter benenson house

1 Easton Street

london wc1x 0dw

united kingdom

www.amnesty.org