By Amir Hossein Asayesh – ZAHEDAN, Iran

Unemployment rate in Iran’s undeveloped Baluchestan province is five times national average.

Blighted by poverty, Iran’s sparsely populated and undeveloped southeastern province of Sistan and Baluchestan has seen an upsurge in violence led by Jundullah, an armed insurgent group that has claimed responsibility for armed attacks on Iranian security forces in the last couple of years.

Blighted by poverty, Iran’s sparsely populated and undeveloped southeastern province of Sistan and Baluchestan has seen an upsurge in violence led by Jundullah, an armed insurgent group that has claimed responsibility for armed attacks on Iranian security forces in the last couple of years.

Iranian officials say the group has links abroad, but there is little doubt the insurgency is also fuelled by a sense of frustration among the Baluch minority, who feel economically deprived and excluded from the institutions of power.

According to the Iranian government’s own statistics, Sistan and Baluchestan is the least developed province in the country. In the last two decades, it has seen the lowest level of investment of any part of Iran. The unemployment rate here is five times the national average, and literacy is also lower than anywhere else in Iran. Nine out of ten people here count as vulnerable, and 45 per cent live below the poverty line.

Located on trade routes with Afghanistan and Pakistan, Sistan and Baluchestan has one thriving industry – smuggling, which involves a wide range of goods and of course Afghan opium and heroin. As a result, Iran’s State Welfare Organisation estimates that drug addiction here is the highest in the country.

News reports in the domestic media only serve to underline that this is Iran’s least stable province. Violence and the drug trade mean that this is also the region that has seen most executions in recent years. Sistan and Baluchestan is Iran’s largest province by area, but is home to just three per cent of its population.

The social system is based around the distinctive customary structures of the Baluch – a traditionally nomadic community who also live in adjoining parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan. They profess Sunni Islam, in contrast to Iran’s Shia majority. Baluch tribal and subtribal groupings like the Rigi, Narui, Shahnavazi, Marri, Kahrazahi, Mobaraki, Sardarzahi, Shirani and Lashari, and the related Brahui people, run day-to-day life, although they are excluded from the highest levels of local government.

Poverty is a longstanding problem in this arid province, but it has been accentuated by a severe drought in recent years. To take one indicator, 30 per cent of girls did not attend primary schools in 2006, a far higher figure than the national average in a country where primary school attendance is compulsory. One reason is the shortage of schools, but another stems from cultural prejudices against educating girls.

Young men, meanwhile, have few opportunities. Unemployment is high, and many work in marginal jobs such as peddling, or simple go elsewhere to work as labour migrants.

Often, though, Baluch men get involved in smuggling, either as small-time traders running Iranian-produced fuel over the border and bringing in contraband goods, or becoming part of bigger international organised crime rings.

Often, though, Baluch men get involved in smuggling, either as small-time traders running Iranian-produced fuel over the border and bringing in contraband goods, or becoming part of bigger international organised crime rings.

This brings them into conflict with Iranian police and border forces patrolling an extended and porous frontier. Smugglers intercepted by the security forces while carrying a few gallons of petrol or sacks of flour by border guards are on occasion shot dead when they try to escape.

Into this mix of poverty, discontent and lawlessness comes a relatively new and dangerous element – Jundollah, the “Army of God”

Into this mix of poverty, discontent and lawlessness comes a relatively new and dangerous element – Jundollah, the “Army of God”

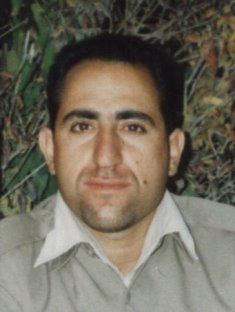

The group, led by Abdolmalek Rigi, combines Sunni extremism, al-Qaeda tactics, ethnic prejudices and ambitious political slogans. It recently renamed itself the Peoples Resistance Movement of Iran, perhaps to avoid being identified too closely with the Pakistan-based Jundollah, an Islamist group with which it is reportedly linked.

The phenomenon of Jundullah and Abdolmalek Rigi has to be seen as a product of pre-existing conditions in Sistan and Baluchestan, and the group feeds off discontentment rooted in a sense of victimhood based on discrimination, humiliation and poverty. In public statements, the 24-year-old Rigi, who has recently assumed the name Abdolmalek Baluch, has claimed that he is fighting to end discrimination, injustice, corruption and what he regards as social engineering designed to tip the ethnic balance in the province against the Baluch. Rigi says Jundullah is a “defensive organisation” that seeks only to “protect the national and religious rights of Baluchis and Sunnis”.

Yet he has proudly claimed responsibility for attacks such as a string of violent acts in the town of Tasuki which left 23 people dead in March 2006. More recently, his group said it carried out a bombing which killed 11 Revolutionary Guards on a bus in the provincial capital Zahedan in February 2007.

Jundullah has copied the tactics used by al-Qaeda in Iraq, such as the brutal murder of captives.

In his most recent statement, issued on December 12, Rigi announced a new operation dubbed “Revenge-3”, and has promised that the current Iranian year (which ends this March) will be the bloodiest yet.

In his most recent statement, issued on December 12, Rigi announced a new operation dubbed “Revenge-3”, and has promised that the current Iranian year (which ends this March) will be the bloodiest yet.

In spite of the horrifying violence employed by his group, Rigi has found supporters, even devotees in Sistan and Baluchestan. A cursory look at certain Baluch private weblogs shows the reverence accorded to him. One blogger called Ahmad Baluch has composed a poem in praise of the Jundullah leader, in which he describes him as the “commander of freedom”, “the symbol of sanctity and manliness”, “the angel of salvation”, and “the bravest of freedom-seekers”.

Iranian officials have consistently accused Pakistan and the United States of covertly backing Rigi, a view shared by some western media outlets which believe Washington is seeking to destabilise Iran in retaliation for Tehran’s interference in Iraq.

Whatever the truth of such allegations of external support, the roots of Jundullah’s popularity among some Iranian Baluchis must be sought inside the country, in a number of festering concerns that affect this community.

Many observers believe widespread poverty and unemployment are significant sources of discontent in Sistan and Baluchestan. According to Maulavi Abdolhamid, the Friday prayer leader and senior cleric in Zahedan, “pressures on the livelihood of the people of Sistan and Baluchestan are so great that they have created public distress”. Another factor that feeds popular discontent is the ethnic policy pursued by the government in Tehran.

Ever since the Islamic Republic was formed, senior officials in provinces that have a significant minority have been selected from outsiders. This unwritten rule applies to local government, police and other security forces in particular, and has been enforced so rigorously in Sistan and Baluchestan that the number of Baluchis and/or Sunnis appointed to “senior director” level over the past couple of decades can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

This situation has led Baluchis to feel that they have no stake in political power. Hossein Ali Shahriari, who represents Zahedan in the Iranian parliament, puts it like this: “In the course of Mohammad Khatami’s second presidential term [2001-05], Sistan and Baluchestan province has had only one Baluch as a county governor, and there hasn’t been a single Baluch or Sunni in the post of provincial governor-general”.

At the same time, Shahriari notes that since Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected president in 2005, Sistan and Baluchestan has had one Baluchi deputy governor-general, five county governors and five director-generals – the provincial equivalent to a minister at national level.

However, this positive shift towards a more inclusive appointments policy has yet to alter the deep-rooted sense of marginalisation in the province. One of the factors that aggravates the situation is that non-Baluchi officials and the local population have found it difficult to reach a common understanding, with the latter perceiving the former as high-handed.

However, this positive shift towards a more inclusive appointments policy has yet to alter the deep-rooted sense of marginalisation in the province. One of the factors that aggravates the situation is that non-Baluchi officials and the local population have found it difficult to reach a common understanding, with the latter perceiving the former as high-handed.

Maulavi Abdolhamid emphasises that the governor-general of Sistan and Baluchestan does not necessarily have to be a Sunni Muslim, but he must be able at least to understand the situation, sensitivities, and concerns of local people.

The Baluchis themselves have psychological blocks about dealing with outsiders. Habibollah, who is a trader based in the town of Saravan, says ordinary people are petrified of any confrontation with the law-enforcement forces, particularly conscripts and junior officers.

A few months ago, Baluchi youths from the city of Iranshahr wrote an open letter to President Ahmadinejad setting out some of their concerns.

A few months ago, Baluchi youths from the city of Iranshahr wrote an open letter to President Ahmadinejad setting out some of their concerns.

“What annoys the Baluch more than anything else is that they are defenceless, they do not have a psychological sense of security, and they do not enjoy the backing either of the law or of those who enforce it,” said the letter, which was published by official Iranian news agencies. “Major academic, cultural and social figures among the Baluch figures have been insulted by non-Baluch conscripts [in the security forces], and not only are these men not reprimanded, they actually receive support and encouragement.”

This sense of insecurity appears to have grown stronger since the March 2006 violence in Tasuki, which led the authorities to impose tighter security arrangements in Sistan and Baluchestan province. These armed attacks had the direct result of provoking a tougher response from government, stark proof of which has been provided by the dramatic rise in the number of executions carried out in the province since that time.

For the average resident, this has made the environment more intimidating than ever. “The current oppressive atmosphere has got to a point where it’s easy to accuse a Sunni Baluch of wrongdoing, of smuggling or involvement in armed groups,” said Abdolaziz, another resident of Saravan.

Religion is another bone of contention, in a country where Shia Islam is dominant and its adherents control all levels of political power. Iranian officials are well aware of the dangers posed by sectarianism and have sought to dampen down divisions between Sunni and Shia. In recent years, the country’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has repeatedly stressed the “brotherhood of Shia and Sunni” and argued that western intelligence services are seeking to exploit and widen the divide. Despite this, many Baluchis feel that parts of the Iranian establishment have acted contrary to the spirit of such remarks.

One Sunni cleric from Zahedan who did not want to be named told Mianeh that he believed it was official policy to change the population structure of this province so as to engineer an increase in the number of Shia adherents.

He added, “Sunnis are in the majority in Sistan and Baluchestan province, yet we are unable to build a new mosque for ourselves, and even refurbishing old ones creates obstacles.”

Amir Hossein Asayesh is a journalist writing on social affairs. This article originally appeared in Mianeh.net

1 comment:

Very interesting blog, you should check out this great blog on Iranian Jews living in America... it deals with many of the same issues your blog covers:

www.jewishjournal.com/iranianamericanjews

Post a Comment